Chapter 5: The Inferential Model of Human Communication

This chapter describes an alternative approach to describing the process of human communication, the “inferential model”. This model addresses many of the issues and shortcomings raised with the traditional “code model” of communication, and offers a newer, and more widely applicable theoretical explanation of human communication processes. This chapter concludes with a summary of how inferential and code models differ in their explanation of human communication.

In the previous chapter, we reviewed traditional models of communication, with a focus on the code model. To date, this way of thinking has been the dominant approach to studying communication across many disciplines, including the discipline of communication. Although this conceptual approach enjoys widespread acceptance and does have some strengths, it also has a number of shortcomings. As a model of human communication processes, the code model has difficulty accounting for many situations that people experience every day, including those where there is not a shared, established code; stimuli are ambiguous; or signals are being improvised. In this chapter, we will try to address these issues by outlining an alternative way to conceptualize human communication, the inferential model (Scott-Phillips, 2015; Sperber & Wilson, 1986).

The Inferential Model

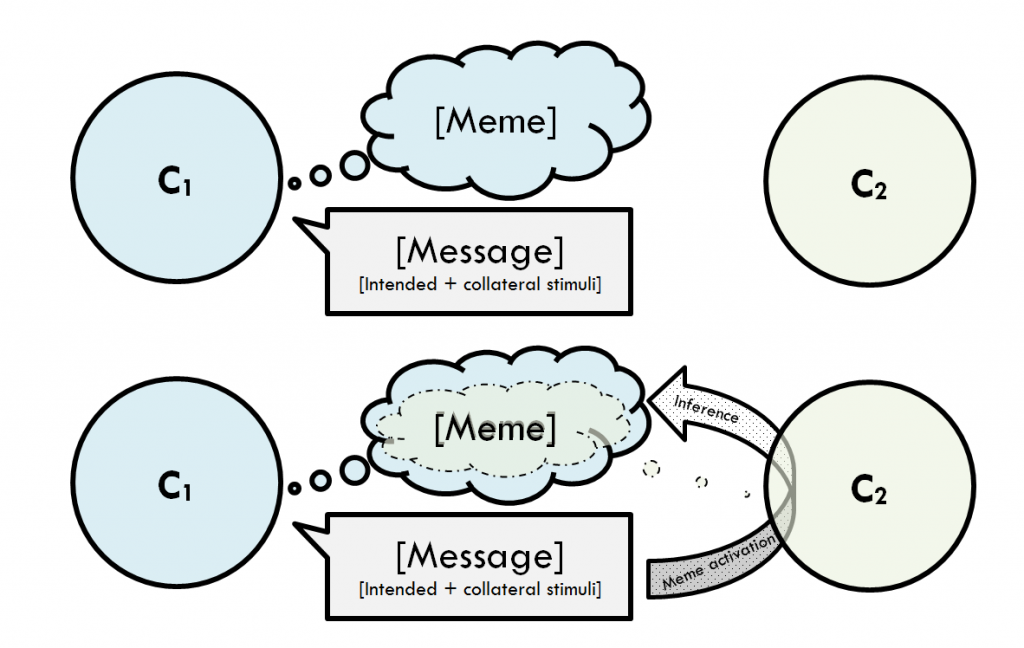

The inferential model proposes that communication consists of communicators making inferences (hence the name) about what the other is thinking or intending based on evidence provided in context. Inferences are essentially deductions or informed estimates. Because we cannot directly read the content of other people’s thoughts, we have to do our best to figure out what they are thinking—that is, the meme states they are intending to communicate—based on their behavior—that is, based on the social stimuli they exhibit. For this process to be successful, communicators have to display and recognize two distinct types of intentions: informative intentions and communicative intentions.

Informative intentions refer to intentions related to the content of one’s meme state—that is, what one is trying to communicate (Scott-Phillips, 2015). When communicators are constructing or sending a message, their informative intention is that their “audience recognize[s] what [they] are trying to communicate” (p. 26). When communicators are interpreting or receiving a message, the informative intention they must infer or recognize is what their interlocutor wanted to communicate or share with them. For example, if Sally wants to tell Anne that, “the toy is in the box”, Sally’s informative intention is that Anne recognizes, or infers, that the particular toy she is referring to is located in a particular box. This informative intention (i.e., that Anne recognize that a particular toy is in a particular box) is what Anne needs to infer for communication of this meme state to be successful. This is generally the set of inferences about intentions that comes to mind first when we think about communicating via inference-making.

Communicative intentions, the second type of intentions, refer to intentions to communicate in the first place. We do many things every day that result in casting many different types of stimuli, but much of it is not intended for anyone, or to communicate anything—it is just incidental, or a by-product of doing other things. For example, when walk down the street, your legs and arms move (as you propel yourself forward) and your gaze moves around (taking in your surroundings), but this nonverbal behavior is not necessarily intended to activate any specific meme states in anyone. However, if you see your friend as you walk down the street, lock eyes with him or her, and start moving in a visibly purposeful way toward them, you could intend your nonverbal behavior to communicate to your friend: “I see you; I am coming over to say hello to you.” In the first example, there is no communicative intention associated with your body movement and gaze; in the second, there is a communicative intention associated with your body movement and gaze. When communicators are constructing or sending a message, their communicative intention is that their “audience recognize[s] that [they] are trying to communicate” (p. 26). When communicators are interpreting or receiving a message, the communicative intention they must infer or recognize is that their interlocutor wants to communicate with them.

Thus, communication depends on two distinct intentions being present and recognized: first, a communicator must intend to communicate (communicative intention), and others must recognize this. Then the communicator must intend for specific meme states to be activated in others’ minds (informative intention). Once other communicators have recognized the communicative intention—and as a result, oriented their attention to the stimuli being provided as relevant to this process—then they must infer the communicator’s informative intention, or what meme state the communicator is seeking to activate.

But how do we manage to infer people’s intentions correctly and appropriately, in context? Given the wide range of things that a single stimulus (for example, waving a hand) could signal or index, how do we possibly arrive at the correct conclusion? (Or at a minimum, the correct conclusion often enough for this to seem like a good idea, as a means of communicating?) Part of the answer is that we accomplish it through cooperation. Communication is an inherently cooperative activity, and successful communication requires collaborative effort, joint attention, and recursive mindreading (a term we will return to) by all involved.

Cooperation and Communication

Cooperation is a term you are almost certainly familiar with; when you read this word, it likely activates memes like “working together”, “mutual effort”, or “teamwork”. These are common definitions of this word, and these can describe what people engage in when they communicate. However, we want to be more precise in our usage of this term. Scott-Phillips (2015) identifies three different types of cooperation involved in human interaction: communicative cooperation, informative cooperation, and material cooperation.

The first of these, communicative cooperation, consists of using stimuli in a way that enables or facilitates communication. This includes (but is not limited to) exhibiting and observing stimuli in interpretable or conventional ways, or using established codes. For example, speaking at an audible volume, using words that fellow communicators know in a conventional way, and providing a sufficient amount of stimuli (to allow others to infer your intended meaning) are all instances of communicative cooperation. Conversely, speaking so quietly that you cannot be heard, using words others do not know, using words in unconventional ways (e.g., saying “dog” to index or signal a plant), or providing insufficient stimuli for successful inference-making (e.g., saying, “see you there” without ever indicating where “there” is) are all acts that could be seen as communicatively uncooperative. We often take communicative cooperation for granted—that is, we assume that others are using stimuli in a conventional manner, and acting in ways that facilitate the creation of understanding (e.g., that they are not saying “dog” to mean “plant”). However, when miscommunication or communicative “failures” occur, it can often be traced back to problems (whether intentional or unintentional) with communicative cooperation.

The second type of cooperation, informative cooperation, consists of activating meme states, or providing evidence for inferences, in a honest and truthful manner. This is, essentially, acting in good faith as a communicator: offering stimuli that reflect a meme state truthfully and accurately, and that do not deliberately mislead other communicators. This type of cooperation focuses on the content that is communicated, and its truth value. Saying, “I’m upset” when you are feeling upset is an example of informatively cooperative behavior (i.e., you are making a truthful statement about your emotional state). Saying “I’m fine” when you are feeling upset is an example of behavior that is not informatively cooperative (i.e., you are making a deceptive or untruthful statement about your emotional state). Generally, what constitutes “truth” is grounded in a given communicator’s perspective: if they are expressing something they believe to be true (even if, objectively, it is incorrect), we would consider their behavior informatively cooperative. Thus, if you say, “The store opens at 10:00” believing the store does indeed open at 10:00, you are acting in an informatively cooperative manner even if the store actually opens at 11:00. (You are just mistaken about the truth value of your beliefs about the store’s hours).

The third type of cooperation, material cooperation, consists of acting in ways that pursue or promote prosocial goals. When someone engages in material cooperation, they are doing things that are considered helpful, positive, or supportive for others. This is probably the type of cooperation that most closely matches your everyday use of the term “cooperation”. Answering a question, complying with a request, offering assistance, or complimenting someone are all materially cooperative behaviors (i.e., they help others, or are actions with prosocial goals and outcomes). Ignoring a question, failing to comply with a rest, denying assistance, or insulting someone are all materially uncooperative behaviors (i.e., they do not help others, or are actions with antisocial goals and outcomes).

These three types of cooperation can occur in different combinations. For instance, it is possible to be communicatively cooperative but informatively and materially uncooperative: telling someone a lie (in a way they can clearly understand), in order to hurt their feelings, is an example of this. Similarly, it is possible to be communicatively and materially cooperative, but informatively uncooperative: telling a lie (in a way they can clearly understand) to save face or protect someone’s feelings is an example of this. It is even possible to be informatively and materially cooperative, but communicatively uncooperative: this can happen, for example, when a technician or specialist offers accurate and truthful advice for fixing a problem, but does so using jargon or terminology we do not know.

To successfully communicate, the only form of cooperation strictly required is communicative cooperation. Without this, it would be close to impossible make accurate inferences about others’ meme states based on the stimuli they provide. To communicate truthful or accurate representations of meme states themselves (or of the state of the world, more generally), however, informative cooperation is also needed. Without informative cooperation, we can successfully communicate, but it is likely to involve deception: in other words, the mutual understanding that is created may involve content that at least one person in the interaction does not believe is true.

Theory of Mind and Mindreading

To engage in the kind of inference-making described by the inferential model, communicators need a special set of skills and abilities. First and most fundamentally, inferring what others are thinking requires what scholars call theory of mind (TOM). TOM refers to the recognition or knowledge that other entities have minds, thoughts, and mental experiences of the world—and that these mental states correspond to (i.e., guide, and are reflected in) their behavior. Implicit in the concept of TOM is also the recognition that others’ thoughts and mental experiences may not be the same as our own—that is, that others can perceive, think, and feel different things than we perceive, think, and feel. Understanding that others have minds, and that others experience the world in terms of their mental states, is fundamental to human social interaction.

TOM shapes our perspective on the world: we instinctively perceive and interpret behavior in terms of mental states and intentions, rather than objective actions. People tend to attribute agency (or lack thereof) to other entities in our environment: that is, we see them as actors or agents that produce particular effects. Closely related, we operate with a basic sense of “goal” psychology, such that we tend to interpret others entities’ actions in terms of trying to achieve some kind of objective. Thus, we see a person waving their hand not as “a waving hand attached to a body” [effect or outcome], but as “a person [agent] greeting us [intention]” or “a person [agent] trying to get our attention [intention]”. Although this most likely evolved as a skill to navigate (increasingly) complex human social environments, TOM permeates our experience of the world to such an extent that we often attribute mental states and intentions to non-human objects as well. If you have ever said something like, “My computer is mad at me” or “That plant is really liking its new spot the garden”, you have engaged in this kind of TOM overgeneralization. Rationally, you know that your computer does not (yet) have emotional experiences that affect its performance, or than a plant is not consciously appreciating its new placement in a flowerbox. However, the language that most readily comes to us, and the interpretation of the situation that is most accessible, is often framed in terms of agents, intentions, and mental states.

This has consequences for communication: when we engage in social interaction, we generally perceive and think about other entities in terms of intentions and mental states. Thus, we do not “see” or interpret social stimuli objectively as actions (e.g., a hand waving, a mouth forming a set of sounds). Rather, we experience them as pieces of evidence, indications, or reflections, of what is going on in people’s minds. Scholars who study this topic refer to the process of inferring what others are thinking as mindreading or mentalizing. Although it is something that many of us do every day (often without even trying), it is in fact a relatively complex, and advanced, social cognitive ability.

According to the inferential model, communication essentially consists of successful mindreading based on social stimuli. Stimuli activate and/or create meme states for us (as in our understanding-focused definition of communication), which we assemble into situation models. For example, we might see someone extending a finger toward an object; this could activate the meme state of “pointing at the object”, and become part of a situation model in which someone is trying to direct our attention to something potentially interesting (i.e., that object). These meme states and situation models, in turn, make up our inferences about others’ mental states – that is, the meme states and/or situation models that others’ have in their minds. In our example, this would be the situation model of directing our attention at an object of interest. (If the stimuli a person provides does not clearly activate any specific meme state, whatever it does activate can serve as a starting point for more conscious or effortful inference-making about that person’s intentions, and therefore their situational model for the interaction).

Mutual Cognitive Environments and Recursive Mindreading

As you read this, you might be wondering how it is that we manage to successfully communicate—that is, create understanding—through inferences, given the wide range of things that a single stimulus could potentially activate. Part of the answer we have given so far is communicative cooperation—that is, communicators use stimuli in interpretable or conventional ways, or use established codified communication systems. But, one could push further, how do we know what stimuli will be “interpretable” to another entity? How do we know how other entities intend for us to interpret the stimuli they provide?

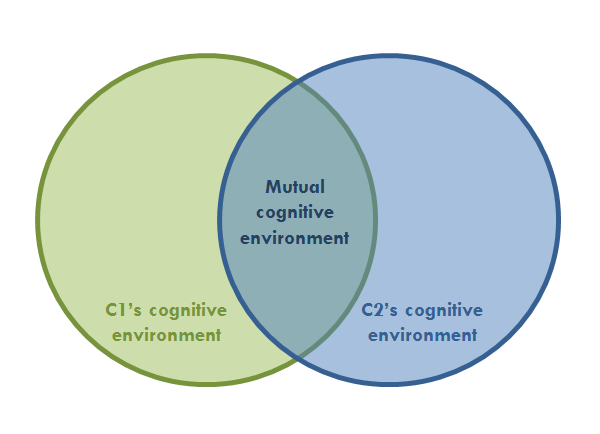

Explaining how we engage in communicative cooperation requires returning to the human mind, and its social cognitive capacities. To successfully make the kind of inferences required for communication, we need to attend to, and be aware of, what fellow communicators know and believe. In other words, we need to be aware of what is in their cognitive environment, defined as “the set of facts [memes] that person is capable of representing mentally, and accepting as true or probably true” (Sperber & Wilson, 1986, p. 39). The content of a person’s cognitive environment may be objectively incorrect or false (e.g., someone might believe a store opens at 10:00, when it actually opens at 11:00), but as long as the person in questions perceives and believes that content to be true, it is considered a part of that person’s cognitive environment. Every person (including you) has a cognitive environment, and its content shaped by that person’s life experiences.

While no two people’s cognitive environments will be completely identical, there will be areas of overlap for any given pair (or group) of people. We can think about these as a Venn diagram: for any two people who come together, there will be a part of their cognitive environments that is unique to each person, and a part that is shared, or common, between them. For example, two sports teammates who come from different backgrounds might have unique memes (i.e., knowledge, memories, and beliefs) about their respective hometowns, politics, or religion. However, as teammates, they have a shared set of memes (i.e., knowledge, memories, beliefs) related to their sport; this is the overlap in their cognitive environment. The “shared set of facts [memes] that two or more people are both capable of representing mentally, and accepting as true or probably true” (Sperber & Wilson, 1986) defines the mutual cognitive environment of those individuals.

To communicate effectively, we need to identify or determine what is in the mutual cognitive environment we share with other communicators, and—critically—what those other communicators (also) think is in our mutual cognitive environment. This recursive knowledge (i.e., “I know that you know that I know”) of our mutual cognitive environment shapes and constrains the stimuli we choose when constructing messages to activate particular meme states, as well as the possible inferences that we make based on the stimuli our interlocutors provide. As a general rule, we presume we are operating within the mutual cognitive environment of which all communicators involved are aware.

When constructing messages, we generally try to choose stimuli that we and fellow communicators are both familiar with (and know we are familiar with), and are linked to memes that are available and accessible to us both (and that we believe are available and accessible to us both). For example, we typically use words that (we believe) others know (and avoid words they do not), and we use those words to signal memes or concepts that (we believe) they know in conversation. If we believe we are introducing a concept or idea (i.e., meme) that our fellow communicators are not familiar with (i.e., is not in our mutual cognitive environment), we generally introduce and explain it using concepts that we believe others do know (e.g., “It’s like X”, “It’s similar to Y”, “It has ABC qualities”).

When interpreting messages, we assume that fellow communicators are using stimuli we are both familiar with (and know we are familiar with), and are linked to memes that are available and accessible to us both (and that we believe are available and accessible to us both). In other words, we presume that people communicate about things they believe we both capable of thinking about, and that they do so in a way that is interpretable to us. Although this might sound obvious, it considerably constrains the possible inferences one could make based on a given stimulus (even an ambiguous one), which is a major issue this way of modeling communication has to address.

So, how do we determine what we jointly believe is in our mutual cognitive environment? This first requires (a) being aware that others have minds (TOM); (b) being able to represent, read, or infer what the content of others’ minds might be (mindreading or mentalizing). However, it also requires an additional set of steps: we need to be able to (c) compare and contrast the content of others’ cognitive environments with our own, (d) represent how our fellow communicators would make this assessment, and (e) represent how they would assess our assessment. The last of these steps is recursive mindreading: inferring what other people infer that we are inferring. When something is recursive, it is characterized by embeddedness and repetition; it involves “the repeated application of a rule, definition, or procedure to successive results”. Thus, recursive mindreading involves reading the content of others’ mindreading.

The concept of recursive mindreading (and indeed, recursivity more generally) sounds difficult and complicated, but is actually something we deal with all the time, and pretty easily, in real life contexts. For example, consider: Do you know what your friends believe you like to do? When talking to a fellow student in your class, do you know (or at least, have a pretty good estimate) of how much they think you know about the course’s material? Do you know what your parents think they know about your personal life? You can probably answer yes for one, if not all, of these situations. All of these situations require a degree of recursive mindreading: you have to know what other people think that you think.

Implications of the Inferential Model

The inferential model was introduced as an alternative to the code model, to address some of the latter’s shortcomings. In this, it succeeds: the inferential model is able to address and explain situations that code model could not: when inferences are the mechanism by which communication occurs, it is possible to communicate successful when there is not a shared, established code, stimuli are ambiguous, or signals are being improvised. Beyond addressing these concerns, however, the inferential model offers a fundamentally different conceptualization, and explanation, of how communication works than does the code model. This has several implications, for both studying communication and the act of communicating itself.

First and perhaps foremost, the inferential model prompts us to think about “meaning” in a different way. In this conceptual framework, “meaning” lies in recognizing or inferring a source’s intentions to communicate, or make common, a particular meme state. The messages (i.e., stimuli) provided function as evidence or signals of those intentions, but they are only that—evidence, or a basis for, an inference. This is an important feature of the inferential model, and one that clearly distinguishes it from the code model. Because meaning depends on inferences about mental states, the use and interpretation of stimuli can be much more flexible. In this model, we are no longer constrained by strictly defined stimulus-meme pairings, or “if/then” rules to decipher messages. Rather, “making sense” or “making meaning” out of a message becomes of a process of inference-making based on the stimuli provided in that message.

Second, and related, the inferential model gives codified communication systems a different role in the communicative process. Rather than being essential to communication, the inferential model positions codified communication systems as helpful, but not necessary, to communication. In inferential model communication, it is the recognition of intentions, not the application of codified communication systems (i.e., systematic associations between stimuli and memes) that is the driving mechanism of human communication. As such, through inferential processes, it is possible to communicate without a (shared) codified communication system. This does not suggest or imply that such systems are unimportant—only that they are not strictly necessary for creating understanding. Indeed, codified communication systems are widely used in human communication, and dramatically increase the efficiency of communication. Because they offer established and reliable associations between memes and stimuli, they drastically reduce the uncertainty associated with inference-making, allowing communicators to make inferences more quickly and be surer of the inferences they are making.

Third, the inferential model suggests that a different set of skills or abilities are required for communication than does the code model. To use a code, or codified communication system, one must be able to represent and apply associations—in the case of communicative codes, associations between stimuli and memes. To make social inferences successfully, however, requires advanced social cognitive abilities: theory of mind, mindreading, and recursive mindreading. This paints a quite different picture of communication: following the inferential model, communication is deeply and fundamentally social, as well as cognitive, in nature. This suggests that these elements require attention in any study of human communication processes, something the code model does not necessarily imply.

Fourth, and related, a focus on inference-making—and particularly, inference making that is supported and enabled by recursive mindreading—characterizes communication as an intrinsically cooperative endeavor. As discussed above, successful inference-making is made possible by the joint attention and joint effort between communicators; this needs both parties. Following from this, the inferential model encourages a shift in focus for the study communication: rather than examining what each individual (i.e., a sender and a receiver) undertakes in a distinct role in communication, the inferential model encourages us to consider the dyad—that is a system of two (or more) communicators—as our unit of analysis. This is consistent with the dialogic, as opposed to monologic, approach to studying communication introduced in Chapter 2.

|

Code Model |

Inferential Model |

|

|

Mechanism |

Application of systematic associations |

Recognition of intentions; inference |

|

Skills required |

Associations |

Theory of mind; recursive mindreading |

|

Meaning |

Property of the stimulus (signal) |

Property of mutual cognitive environment |

|

Process |

Match stimuli with meme |

Make informed hypotheses based on evidence in context |

|

Codes |

Necessary |

Helpful |

|

Focus |

Individual (one mind) |

Coordinated dyad (two minds) |

Fifth and finally, by positioning inference-making as the core process defining communication, this model suggests that all communication is intrinsically uncertain, inexact, and to a degree, indeterminate. We are essentially playing an ongoing social guessing game, doing the best we can to make informed deductions based on the evidence at hand. However, since we do not have direct access to others’ minds, we can never be completely sure that our meme state matches that of our fellow communicators—an observation that should perhaps give us all some pause, and patience, as we interact with others.

References

Scott-Phillips, T. (2015). Speaking our minds. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.