7 Census Data

Gwen Sinclair

Learning Objectives

- Understand the purposes of the Decennial Census of Population and Housing, the American Community Survey, and the Economic Census

- Become familiar with what kinds of data are collected in the census surveys and the most important data products

- Understand what a librarian needs to know about some of the issues and limitations surrounding census geography, race and ethnicity categories, and aggregation of data

- Gain awareness of commercial databases that repackage census data

- Learn where to find historical census data

Introduction

“60 million people live in the path of hurricanes.”

“The nation is aging, but some counties are getting younger.”

“Rural economy extends beyond the farm.”

“More women in early 30s are childless.”

“Which states spend the most money on their students?”[1]

All of the headlines above are tied to data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau, part of the Department of Commerce. The Census Bureau conducts hundreds of surveys each year. The best-known is the decennial census, which has been conducted every 10 years since 1790. Although the primary purpose of the decennial census is to provide an enumeration of the U.S. population for the apportionment of the House of Representatives, the scope of the data collected in census surveys, and their frequency, has been expanded over the past 200 years to encompass many topics, from mining to local government to internet use. Millions of researchers rely on census data to provide basic demographic and economic statistics, base maps, and other data. But census data is not designed for casual users; it requires some expertise and background knowledge, and librarians play a crucial role in helping users to find, use, and understand the data.

Historical Overview of the Decennial Census

We’ll begin with an overview of how the federal decennial census has been conducted and how questions have been added to the surveys over time. Prior to 1960, enumerators went to residences, asked questions, and recorded answers on enumeration sheets. These enumeration sheets were used until 1970, although in 1960 forms were mailed to most households. Looking at the forms and the instructions to enumerators can help you to understand what kind of data you can get from the census. In addition to their use for genealogical research, enumeration forms can be used to document residence at a particular time and place or get a demographic picture of a community, among other things.

How accurate is census data? If you think about how censuses are conducted, it’s almost certain that some people weren’t counted, especially if there was no follow-up. In addition, errors were introduced by incorrect transcription on the part of the enumerator, language barriers, and reluctance on the part of some individuals to respond to the census for a variety of reasons. Still, it’s the most comprehensive demographic survey in the U.S.

The Decennial Census from 1790 to 2000 explains all of the questions asked in each census through 2000.[2] Early censuses asked only a few questions: How many people live in this household? What are their ages, sexes, and races? These were the basic questions required to determine the size of the electorate at the time. Recall that for much of the history of the U.S., nonwhites and women did not have the right to vote, and of course children still do not have the right to vote. Enumeration methods have varied, including how African Americans, both free and enslaved, and Indians were counted. Before 1930, Congress determined which questions would be asked in the Census, but in 1930 formulation of questions was delegated to the Department of Commerce, although the Census Bureau is still required to inform Congress of the questions it intends to include.

The 1820 census added a question asking in which economic sector (agriculture, commerce, or manufacturing) the inhabitants were occupied. In 1830, questions about disabilities and citizenship were added. Literacy became the subject of a question in 1840, and the 1850 census added questions about a person’s occupation, his or her place of birth, and the value of any real property. Also in 1850, the individual, rather than the household, became the unit of data collection. In addition, people who were likely to require social assistance, such as deaf or blind people or the criminally insane, were tabulated.

As immigration became more of an issue in the late 19th century, questions were added regarding language and national origin of both the respondent and his or her parents. In 1880, questions about marital status and relationship of the respondent to the head of the household were included. One can see how the census reflected the concerns of society as questions about the proportion of Indian blood and age at first marriage were included in 1930. Also in 1930, a question about technology, asking if respondents had access to a radio, was included to help the government assess the potential of using radio broadcasts during emergencies. Starting in 1940, in addition to the basic census questions, sampling was introduced to gather additional data about a sample of the population. This led to a trend of longer and longer surveys for the sample, which were sent to a portion of all households. In 1940 the first census of housing was implemented. Its purpose was to evaluate the state of housing following the Great Depression, when little new housing had been developed. 1940 is also when the place of residence in the previous year was added to allow tracking of migration, and income was also added. Furthermore, the 1940 census was the last for which the results were publicly available following tabulation. Subsequently, the information has been kept confidential for 72 years following each survey. Individuals can request their own or their immediate relatives’ census documents for purposes of documenting residence.

With greater urbanization, in 1960 questions about place of work and means of transportation to work were added. As Latinos became a greater portion of the population, the census added a question about Spanish origin or descent in 1970. By 2000, a question about grandparents as caregivers had been added, and respondents were able to choose multiple race categories for the first time. In 2010, same-sex marriage was included as an option (previously, same-sex couples were not treated as couples). With current research into gender fluidity and new understanding of gender identity, it’s possible that someday people will be able to choose something other than male or female.

As the 2020 decennial census approached, controversies raged. To save money, the Census Bureau arranged to have the census completed online rather than mailing printed forms to each address. A proposal to add a question about citizenship, which had been dropped from the census decades earlier, generated protests and lawsuits. Each year it becomes more difficult to get people to respond to the census. There are a variety of reasons for the declining response rate. Some individuals fear that the information they provide on a census form could be used against them. Some are opposed to the government and refuse to participate in its information gathering activities. Others are frustrated by having to choose from categories that they feel do not represent their self-identity or living situation. For some, language or literacy are barriers, even though census forms are printed in a number of languages. Libraries served as an integral part of outreach for the 2020 Census (see Libraries and the 2020 Census.).

Additional Topics

Race and Ethnicity in the Census

In the 1850 Census, there were only three possible racial categories: white, black, or mulatto (one-half Black). Given that there were many Latinos and a few Asians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. in 1850, one may wonder how the enumerators categorized them. Mexicans, as it turns out, were counted as white. A search in Ancestry.com for people who had lived in Hawaiʻi who were born in 1792 revealed an enumeration sheet from the 1850 Census showing several miners in Calaveras County, California, who were from the Sandwich Isles. The race column had been left blank.

In 1880, a special enumeration was made of Indians living on reservations, although Congress did not appropriate sufficient funds, so it was not completed. Indians were categorized as “taxed” and “not taxed” to differentiate those living away from reservations from those living on reservations. These enumerations can be very important in documenting tribal affiliation, which may be needed to enroll as a member of the tribe.

Racial categories in 1880 were white, Black, mulatto, quadroon (one-fourth Black), octoroon (one-eighth Black), Chinese, Japanese, or Indian. The addition of Chinese and Japanese indicates that these groups were large enough to warrant a separate category for each. The different gradations of mixed-race African-Americans were included because of a belief that pure African-Americans were dying out. Evidently, not all enumeration sheets included the same racial categories. An enumeration sheet in Indiana, for example, did not include a race category for Japanese.

In 1920, Filipino and Korean were added as choices. Other ethnicities still had to be written in on the enumeration sheet. In 1930 the “one drop” rule for classifying individuals with African ancestry as negro was instituted. Previously, those of mixed race were classified as Black, mulatto, quadroon, or octoroon, but racial attitudes in the 20th century dictated that anyone with any amount of African ancestry was Black.[3] Also in 1930, Mexican and Hindu were added as race categories, although later they were dropped. In 1970, the question, “Is this person of Spanish/Hispanic origin or descent?” was added. It’s important to note that a person of Latino ancestry can be of any race — Hispanic or Latino is not a race in the context of the Census questionnaire.

Discrepancies in the race and ethnicity categories used by various federal agencies led to an interagency working group that proposed standard racial categories which were adopted in 1977 in Statistical Directive 15 of the Office of Management and Budget. It “mandated a minimum standard for all federal data collection [and] recommended a racial classification with four categories (American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian or Pacific Islander; Black; White) and a Hispanic classification with two categories (Hispanic origin; not of Hispanic origin).”[4]

By 1980, race categories had been greatly expanded to include Hawaiians and some Pacific Islanders, and American Indians were distinguished from Inuit and Aleut people. Finally, in 2000, individuals could choose more than one race and were permitted to write in specific ethnicities. Nonetheless, the Office of Management and Budget, which determines standards for data collection in the federal government, only requires federal agencies to give five choices: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, often referred to as NHOPI. Members of advisory groups to the Census Bureau from Hawaiʻi have lobbied the Bureau to separate Native Hawaiian from Other Pacific Islander because researchers need data for Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Island ethnic groups alone. Similarly, Asian groups would like to see a requirement that specific Asian ethnicities be required as choices, since aggregating all Asians is not helpful in understanding trends related to specific ethnic groups. Surprisingly, there is no option for persons of Middle Eastern ancestry to identify themselves. Census data users may also be confused by the inclusion of a category labeled “Ancestry,” added in 1980, that only lists European ancestries.

Housing

Since 1940, the census has included questions about housing. The decennial census includes a question asking whether the respondent owns or rents a home. The Census Bureau also tallies the number of housing units in order to create a picture of the state of housing in the U.S. Each question in all of the Census Bureau’s surveys is included to gather data for specific purposes. Two years prior to each decennial census, the Census Bureau prepares a report for Congress about the questions it will include in its surveys.[5] The question “Does this house, apartment or mobile home have a flush toilet?” more than any other, generated anger among respondents to census surveys. The question appeared in the American Community Survey (ACS) as an indicator of housing quality, but critics have viewed such questions as an invasion of privacy and unrelated to the main purpose of the census. While the question about toilets has since been dropped, ACS still asks about home heating, housing costs, home ownership, home value, rent paid, plumbing and kitchen facilities, number of rooms, and year built. The Census Bureau conducts the biennial American Housing Survey on behalf of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The survey collects information about housing inventory, the condition of America’s housing stock, mortgages, home values, neighborhood quality, and other indicators.[6]

Language

Census data users are sometimes frustrated to learn that they cannot obtain demographic data for speakers of less common languages. According to the Census Bureau,

Due to small sample counts, data tabulations are not available for all 1,333 languages. Presenting data for all language codes is not sensible due to confidentiality concerns. Therefore, the Census Bureau collapses the languages into more manageable categories for tabulations. The original language categories were developed following the 1970 Census and were based generally on Classification and Index of the World’s Languages (Voegelin, C.F. and F.M., 1977). In the American Community Survey, the language categories have been updated, with the latest revision occurring in 2016.[7]

Imagine that a researcher wants to learn how many Ilocano speakers are in Honolulu County. He would find that Ilocano speakers are aggregated with speakers of Samoan, Hawaiian, and other languages, whereas Tagalog is reported separately. Furthermore, the data is only available for the entire state, not for counties.

Historical Aggregate Census Data

Patrons often want downloadable census data and may not be satisfied with print or digital page images of tabular data. The Census Bureau has digitized many of the old census volumes as page images, but data prior to 1990 is not downloadable from their website. Unfortunately, the Census Bureau hasn’t digitized all of the volumes related to the U.S. territories. This means that we still rely on print or microfilm for some of the statistics about Hawaiʻi, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and other possessions.

The National Historical Geographic Information System provides access to downloadable historical Census data going back to 1790, but usually only for states or counties. ICPSR, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, has an astonishing number of census data sets. Bear in mind that many of these data sets do not go down to the smaller geographic areas like census tracts that many patrons need.

American Community Survey

Between 1940 and 2000, the decennial census consisted of a short-form questionnaire that was sent to most households and a long-form questionnaire sent to a sample of households, most recently to one out of every six households. Beginning in 2010, the Census Bureau eliminated the long form in the decennial census and implemented the American Community Survey to replace it. ACS samples a smaller portion of the population annually and was launched in 2001 as a test prior to the full implementation in 2010. The ACS enabled the Census Bureau to save money by reducing the number of surveys it sent out and it also made it possible to collect more current data. The down side to the ACS is that one year of data does not sample a sufficiently large number of households to be valid for smaller geographic areas like census tracts, so users must use five-year data for smaller geographies, which means that the data is not as current. Furthermore, the questions asked in ACS change from year to year, so it is not always possible to compare data. Nevertheless, researchers rely on ACS data for socioeconomic characteristics that are not covered in the decennial Census. Table 1 compares ACS data with the Decennial Census.

Table 1. Comparison of American Community Survey 1- and 5-year estimates and Decennial Census.[8]

|

American Community Survey (ACS) |

Decennial Census |

|

|

1-year estimates |

5-year estimates |

10-year (count) |

|

Example: 2015 ACS 1-year estimate |

Example: 2010-2014 ACS 5-year estimate |

Example: 2010 Decennial Census |

|

Dates collected between: January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015 |

Dates collected between: January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014 |

Date collected: April 1, 2010 |

|

Smallest sample size |

Larger sample size |

Counts every person |

|

Data for geographic areas with population larger than 65,000 (counties and metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in |

Data for geographic areas down to Census tract |

Data for geographic areas down to Census block |

|

Highest margin of statistical error |

Smaller margin of statistical error |

Smallest margin of error |

|

Most current data |

Less current data |

Currency depends on time elapsed since the Census was taken |

|

BEST USED WHEN |

BEST USED WHEN |

BEST USED WHEN |

|

Data currency and/or detailed population characteristics are more important than geographic precision |

Geographic precision is needed over currency of data |

Smallest geographic areas needed and data is not available in ACS |

|

For Hawaiʻi, you are limited to state, county and MSA |

Select geographic areas like Census tracts, zip code tabulation areas, and Hawaiian Homelands |

Examine population down to the Census block group or block level |

Apportionment of the House of Representatives and State Legislatures

A question that comes up from time to time in the context of the Census of Population is, exactly whom do our representatives in Congress represent? Currently, the population used for apportionment of the House of Representatives is the resident population, including both citizens and noncitizens and members of the armed services, even if they are stationed overseas. A person’s usual residence is defined in regulations, which may be revised periodically. The regulations give specific guidelines about how to count visitors, college students, and people who have no usual place of residence.[9] Because the District of Columbia is not a state, it does not have a voting representative in Congress and it’s not included in the apportionment count.

States usually have an appointed commission that draws legislative district boundaries following each decennial census. In Hawaiʻi, the state legislature is apportioned by the Reapportionment Commission, which has the authority to decide how to define the resident population of the state. Each year ending in 1 is a reapportionment year. In 2011, there was quite a bit of back and forth about how college students and members of the armed services should be counted, because obviously those groups would swell the population of the islands and districts in which they live.

From the review above, you should have a good sense of what kinds of data are collected. It’s also important to be aware of information that cannot be found in census data. Although special censuses of religious establishments were done in the past, it’s no longer a part of the census program. Aside from questions about disabilities, the census doesn’t cover health conditions. It has included some vital statistics questions like number of children ever born, but those types of questions are no longer included in the census and the information is obtained from records. Some family relationships have not been covered, such as same-sex relationships, and the census doesn’t have a category for relationships like foster parents or hānai children. Finally, although the data may have been collected, published reports often aggregate data in frustrating ways, such as lumping Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders together, or reporting age by groupings that don’t align with what the researcher wants.

Privacy and Confidentiality

The responses provided to the Census Bureau in its surveys are confidential and by law cannot be shared with other government agencies or individuals. It wasn’t always so, though. In the days immediately before and following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Census Bureau provided information to military authorities about the numbers and locations of persons of Japanese ancestry, data that would be used to round up and incarcerate these individuals in internment camps.[10] Fortunately, census privacy was consolidated into Title 13 of the U.S. Code in 1954.

Today, the Census Bureau goes to great lengths to protect the privacy of its data. Sometimes frustratingly for census data users, “disclosure avoidance” measures are used to prevent disclosure of confidential data. These include statistical methods to prevent data users from being able to identify individual respondents in cases where it would be possible to identify someone based on their responses. The Bureau also implemented a new mathematical method of protecting privacy, called differential privacy, for the 2020 Census.[11]

Case Study: Census Data and Privacy

by Ashley Forester

Learning Objective: Demonstrate how to use government and non-profit websites to effectively answer a question about privacy rights in the census.

Question: I am concerned about the 2020 census and heard about the citizenship question possibly being on the census. I am wondering how the data from the census will be used and how my privacy will be protected.

The main Census Bureau website provides an overview of the census and what it entails. Under the Surveys/Programs tab, there is a link to the 2020 census website. It has information about privacy and security as well as why a person’s answers matter and how the Census Bureau protects everyone’s data. The site explains the importance of the data as well as the impact on the local community. The data collected from the census helps businesses, researchers, and communities make decisions. The data can help determine where a community needs a new fire department, or whether additional funding is needed for school lunches or new roads, for example. The data from the 2020 census will also help determine how billions of dollars in federal funding flows into states and communities each year.

An individual’s privacy is protected because the Census Bureau is bound by Title 13 of the U.S. Code to keep respondents’ information confidential. Under Title 13, the Census Bureau cannot release any identifiable information about a person, their home, or business, even to law enforcement agencies. The law ensures that everyone’s private data is protected and that their answers cannot be used against them by any government agency or court. The answers they provide are used only to produce statistics. Their answers are kept anonymous and the Census Bureau is not permitted to publicly release anyone’s responses in a way that could identify them or anyone else in their home.[12]

To find the answer about a question about citizenship status on the census form, consult the U.S. Supreme Court’s website to find the most recent ruling on the subject. In the top left corner of the page, there is an Opinions tab and under that is the Opinions of the Court tab. In the list of 2018 decisions, the document entitled “Department of Commerce v. New York” dated June 27, 2019 provides the court’s ruling that a citizenship question shouldn’t be included in the 2020 census. [13]

To show how the census data translates into federal money for states, the Census Counts website allows you to view a state-by-state map that shows not only how much federal money went to each state, but also which specific programs benefited from the federal money that was allocated based on the previous census in 2010. For example, Hawai‘i received over $3 billion dollars following the 2010 census. [14]

This case study demonstrates how official government information may be combined with information from a non-profit organization to provide a more complete and easily understandable answer.

Census Geography

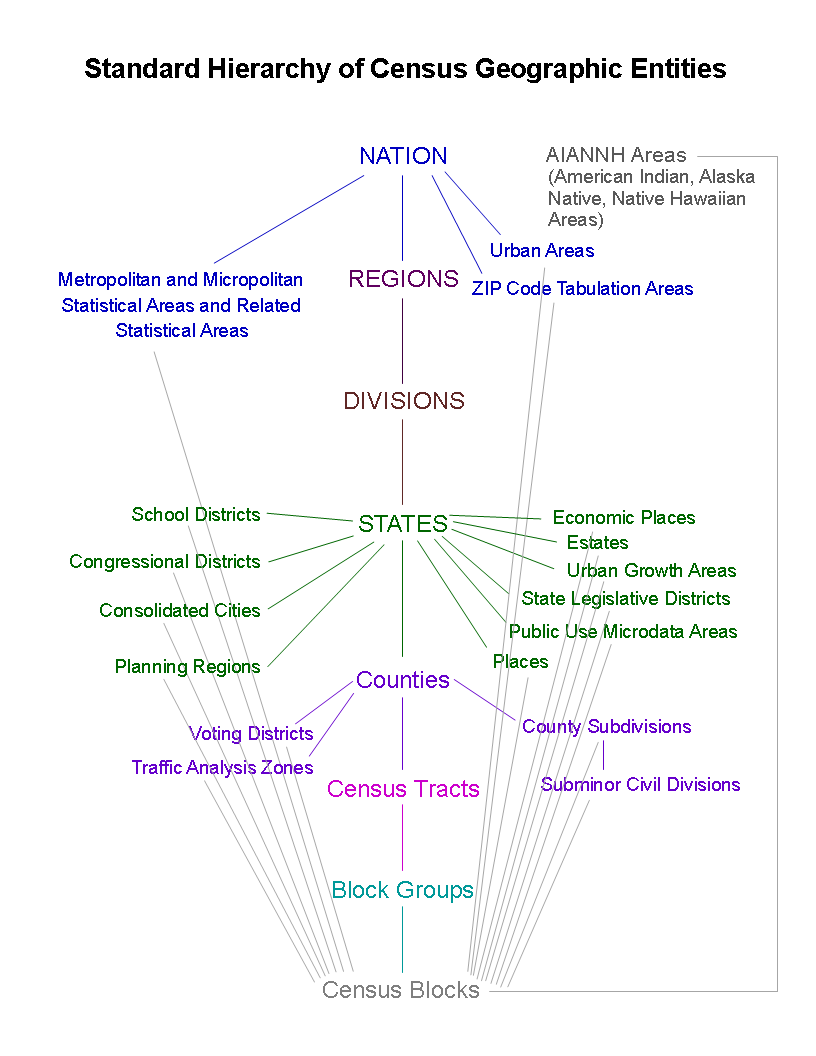

The Census Bureau has developed a hierarchy of geographic areas for which data may be released (Figure 1).

The census tract is an artificial geographic statistical area created specifically as a stable way to report statistics about areas like neighborhoods. Census tracts are intended to have approximately the same population, so some tracts cover more area than others. Tracts are sometimes split into smaller tracts in areas of rapid population growth. Initially, census tracts only covered 25 percent of the land area in the U.S., but by the 2000 census all counties were subdivided by census tract.[15] Because tract numbers can change over time, it is sometimes difficult to compare tract-level statistics from different decennial censuses.

Users of ACS may be frustrated when the data they seek is restricted due to data suppression. Data may be withheld due to confidentiality concerns (in other words, releasing the data would allow someone to identify a specific respondent); data reliability (insufficient data is available to provide a reliable sample); data quality (small sample size); insufficient number of cases; and microdata errors.[16]

Population thresholds further limit the availability of ACS data. For one-year estimates, which are based on a single year of ACS data, there is a population threshold of 65,000 persons. In other words, for geographic areas with a population less than 65,000, no data will be reported. As a result, in Hawaiʻi, one-year estimates are only available for Honolulu and for counties, but not for county subdivisions, other towns, or census tracts.

Census Geography in Hawaiʻi

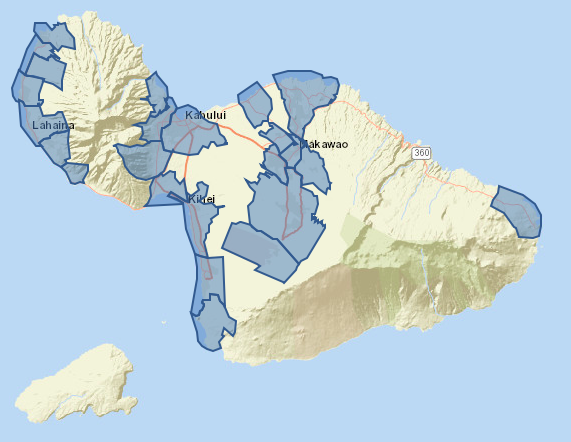

There are a few things you should know about census geography in Hawaiʻi. First, since there are no incorporated towns in the state, we rely on census-designated places, or CDPs, to function like towns. If we look at the CDPs on Maui (Figure 2), we can see that they correspond pretty well to what we think of as communities on Maui, although some of the smaller communities like Ke‘anae are missing.

Islands are not a type of census geography. If we want data for an island like Molokaʻi, we must use county subdivisions. The island of Lānaʻi is a county subdivision, and Molokaʻi is comprised of three county subdivisions: west Molokaʻi, East Molokaʻi, and Kalawao. Kalawao, which encompasses the Kalaupapa peninsula, is also its own county for census purposes. Because there is a single statewide public school system in the state, it doesn’t make sense to look at census data by school district in Hawaiʻi as it would in the continental U.S. In addition, Hawaiʻi includes a geographic subdivision that exists nowhere else, Hawaiian Home Lands, but populations may be very small so some data may be suppressed due to population thresholds.

Finding Current Census Data

Data.census.gov is the search interface used for all census data from the 2000, 2010, and 2020 decennial censuses and the American Community Survey and economic censuses going back to 2010. It operates using a broad search that can be narrowed through the use of facets. More advanced researchers can use the advanced search function, which allows a user to browse through topics, geography, and other elements to construct a search. Finding census data is not intuitive and users frequently require help in finding the specific data they require, or they need to be advised about whether the desired data is actually available. Basic tutorials on census data are available on the Census Bureau website. The Census Bureau produces many webinars that make it easy to refresh your skills if you are only an occasional user of census data. Many webinars conducted by Census Bureau employees or librarians are also available through the FDLP Academy and North Carolina Library Association’s Help! I’m an Accidental Government Information Librarian webinar series.

The Census Bureau has produced many special reports, briefs, and technical reports throughout its history, ranging from reports about business sectors to illiteracy. State Data Centers, a network of state offices that partner with the Census Bureau to serve as a conduit for census data and provide training to users, also perform special tabulations and produce customized reports for local audiences, and they have access to historical data sets, for which librarians occasionally receive requests. You can also request that the Census Bureau do a special tabulation, but there is a fee for that service.

Public Use Microdata Samples (PUMS)

PUMS are samples of census data that allow users to create their own tabulations. Access to PUMS data is available through data.census.gov. Another way to access PUMS data is the Minnesota Population Center’s IPUMS site, which allows users to create tabulations from the decennial censuses from 1850 to 2010 and ACS from 2001-present or to combine data from different datasets. Users are required to create a free account to use IPUMS.

Other Censuses

Census of Agriculture

The Census of Agriculture was conducted by the Census Bureau from 1820 through 1992, when it shifted to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA’s Census of Agriculture site contains the text of all of the historical Census reports. You can also find downloadable data on the ICPSR site mentioned above. The Census of Agriculture primarily reports the number of farms, value, acreage, characteristics of farmers and farm laborers, irrigation, machinery, and types and value of farm animals and crops grown. In addition, it covers irrigation, water resources, and farm energy production, among other topics. Reports are customized for states, so each state’s reports do not necessarily list the same commodities or ethnicities as other states. A complete list of current surveys can be found on the National Agricultural Statistics Service website.

Economic Census

This section will give an overview of the most important current and historical surveys and business-related Census products. In addition to the products listed below, the Economic Census also includes surveys of construction, mining, manufacturing, and state and local governments.

The census has asked questions about manufacturing activity since 1810, but a separate economic Census did not begin until 1905. The modern Economic Census is conducted every five years in years ending in 2 and 7. The Census Bureau currently conducts 40 different surveys of business in addition to surveys of population and housing.[17] As with the Census of Agriculture, census forms are customized for different industries. The Economic Census primarily collects data about business establishments (a business or industrial unit with a single geographic location) with employees. In other words, it excludes businesses without employees, such as child care providers, used car dealers, real estate operators, and the like (but these may be covered in other surveys). It also collects data about industries, which are classified according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). It’s important to note that the Economic Census does not cover all of the industries in the NAICS classification.[18] Generally, agriculture, government, and rail transportation are not included.

Data is available for the United States as a whole, states, and to a lesser extent counties, metropolitan areas, zip codes, and places with 2,500 or more inhabitants, but not for census tracts or blocks. While more or less the same data has been collected for the duration of the Economic Census, it has not always covered all sectors of the economy. For example, some transportation industries, insurance, real estate, and finance were not covered until 1992. In contrast to the Census of Population and Housing, the enumeration forms for economic surveys are not retained by the Census Bureau after the data has been tabulated. Data from 2012 to the present is available in Data.census.gov.

The Economic Census does not provide information on occupations, although it publishes data on employees by occupation for selected industries. The Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes data by occupation, and the American Community Survey also publishes some labor force and occupation data.

Consumer Expenditure Survey

The Consumer Expenditure Survey collects data on behalf of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) about how much consumers spend on rent, food, and other necessities. The data is available on the BLS website, but only for larger geographic areas like counties and cities. Consumer expenditure data is collected for BLS in the Interview Survey, which includes major and/or recurring items, and the Diary Survey, which covers minor items. The data collected in these surveys feeds into the calculation of the Consumer Price Index.[19]

County Business Patterns (CBP)

CBP is an annual series, started in 1964, that provides economic data by industry for counties, zip codes, congressional districts, and metropolitan areas. It includes the number of establishments, employment during the week of March 12, first quarter payroll, and annual payroll.[20] Using CBP data, one can learn which counties are gaining or losing jobs and in which industries those jobs fall, for example. CBP combines data in the Business Register (BR) database, which contains all known employer business establishments in the U.S., with Economic Census and the Company Organization Survey (COS).

Census Business Builder (CBB)

CBB is a group of services that provide selected demographic and economic data for specific users, such as small businesses, regional planners, and chambers of commerce. The Small Business Edition presents information for small businesses that are planning or expanding their business. Available information includes demographic data, economic data from CBP and other surveys, imports and exports, consumer spending, agriculture data, and workforce data.[21] Regional Analyst combines demographic data, CBP, consumer spending, Census of Agriculture, and workforce data.[22] It’s the best tool for users who need to aggregate data from different sources. Demographic and consumer spending data are available at the state, county, city/town (“place”), ZIP Code, and census tract levels. Economic and workforce data are available at the state, county, and city/town levels.

USA Trade Online (UTO)

Import and export quantities and value are available for countries, states, and ports through the UTO interface. UTO is free, but requires users to sign up for an account. Ports include trade through airports, pipelines, roads, railroads, mail, and sea-based ports. Imports are classified according to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule, while exports are classified according to the NAICS code and are therefore less granular. A parallel product is the U.S. Imports of Merchandise and U.S. Exports of Merchandise DVDs, which may be found in large research libraries. For the most part, the DVDs provide access to the same data as UTO, but they also contain additional data and functionality.

Retail and Wholesale Trade

The Census Bureau publishes a wealth of information about retail and wholesale trade industries, including:

- Sales

- Inventory

- E-commerce sales

- Operating expenses

- Employees

- Payroll

- Number of firms[23]

Business Dynamics Statistics (BDS)

BDS provides measures of changes in business activity such as startups and closures and job creation/elimination. It also provides analysis of entrepreneurship, business survival, and employee turnover.

Survey of Business Owners and Self-Employed Persons (SBO)

Formerly done every five years, the SBO is now an annual survey of the characteristics of business owners, such as sex, race, and veteran status. It covers non-farm businesses that file any kind of federal tax return.

Mapping Products

The Census Bureau has created several interactive mapping tools that allow users to create their own thematic maps. They include:

- Census Data Mapper—Allows users to create maps using Census 2010 data

- On the Map—Shows where people work and live to illustrate geographic patterns of employment

- Other mapping topics include rural America, poverty, emergency management, and health insurance

Librarian’s Library

Gauthier, J. C. (2002.) Measuring America: The decennial censuses from 1790 to 2000. http://www.Census.gov/history/pdf/measuringamerica.pdf

Contains all of the questions asked in each decennial Census.

Anderson, M. 2015. The American census: A social history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Detailed review of the questions asked in each census and the social conditions that influenced changes in how the census was conducted.

Dubester, H. J. 1968. Catalog of United States Census publications, 1790-1972. New York: Greenwood Press.

Indispensable guide to historical census reports and statistics.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1994). Geographic areas reference manual. https://www.Census.gov/geo/reference/garm.html

Explains census geography in minute detail and discusses data confidentiality thresholds.

Ockert, S. (Ed.). (2019). Business statistics of the United States: Patterns of economic change (23rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Bernan Press.

This annual publication compiles business and economic statistics from World War II to the present. Topics covered include income, GDP, poverty, consumer spending, imports and exports, wages, and employment.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Topics. https://www.Census.gov/ ↵

- Gauthier, J. C. (2002.) Measuring America: The decennial censuses from 1790 to 2000. http://www.Census.gov/history/pdf/measuringamerica.pdf ↵

- Bennett, C. (2000). African-origin population. In Anderson, M. J. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ↵

- Anderson, M. J. (2015). The American Census : A social history. New Haven: Yale University Press, 231. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2018. Questions planned for the 2020 Census and American Community Survey. https://www.Census.gov/library/publications/2018/dec/planned-questions-2020-acs.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Housing Survey (AHS). About. https://www.Census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/about.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. About language use. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/language-use/about.html ↵

- Barr, A. (2016). HLA Census workshop 2016. https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=559028&p=3844995 ↵

- Office of the Federal Register. 2020 Decennial Census residence rule and residence situations. 80 FR 28950. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/05/20/2015-12118/2020-decennial-Census-residence-rule-and-residence-situations ↵

- Anderson, M. J. (2015). The American Census: A social history. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. Ebook. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Disclosure avoidance and the 2020 Census. https://www.census.gov/about/policies/privacy/statistical_safeguards/disclosure-avoidance-2020-census.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. How the Census Bureau protects your data. https://www.2020census.gov/en/data-protection.html ↵

- U.S. Supreme Court. (2019). Supreme Court syllabus. Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/18pdf/18-966_bq7c.pdf. ↵

- Census Counts. (n.d). Hawaii. https://censuscounts.org/state/hawaii/. ↵

- Salvo, J. J. (2000). Census tracts. In Anderson, M. J. (Ed.). (2012). Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). American Community Survey data suppression. http://www2.Census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/tech_docs/data_suppression/ACSO_Data_Suppression.pdf?# ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. Surveys & programs. https://www.Census.gov/programs-surveys/surveys-programs.html ↵

- Zeisset, P. T.(2000). Economic Census. In Anderson, M.J. (Ed.). (2012). Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ↵

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer expenditure surveys. https://www.bls.gov/cex/#products ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. County business patterns (CPB). https://www.Census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census Business Builder: Small Business Edition (CBB:SBE) v. 2.3. https://www.Census.gov/content/dam/Census/data/data-tools/cbb/sbe-flyer.pdf ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census Business Builder: Regional Analyst Edition (CBB:RAE) v. 2.3. https://www.Census.gov/content/dam/Census/data/data-tools/cbb/rae-flyer.pdf ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. Guide to data sources from the U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.Census.gov/econ/wholesale.html ; Guide to data sources for retail trade from the U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.Census.gov/econ/retail.html ↵

Statistics on births, deaths, marriages, and divorces.