17 Freedom of Information and Open Government

Gwen Sinclair

Learning Objectives

- Become familiar with classification and declassification practices

- Understand the purpose and limitations of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Examine the aspirations and reality of open government

- Gain awareness of state government information practices

Introduction

Freedom of information, in general, refers to the inherent right of individuals to have access to information. In the context of government information, freedom of information refers to the rights of citizens to know what the government is doing and to view government records. That being said, in the federal government access to information is largely driven by politics. The president is responsible for setting policy regarding government secrecy and openness in the executive branch. Some presidents have tended to believe that government secrecy is necessary to maintain national security, while others have tried to establish more liberal policies. In addition, Congress and the courts have important roles when it comes to freedom of information legislation and enforcement of laws relating to open government. Ironically, access to information about the deliberations and behind-the-scenes decisionmaking in the judicial and legislative branches is practically non-existent.

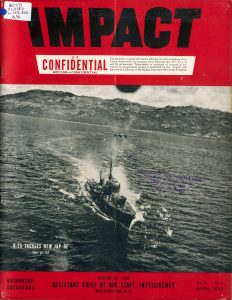

Security Classification

Classification refers to the practice of designating security levels for types of information or individual documentation. Documents may be classified as confidential, secret, top secret, or restricted data (a classification used by the Department of Energy). Classification and declassification is ultimately determined by the president’s policies. Agencies use classification manuals to apply classification schedules. Classified information it is subject to declassification schedules that mandate automatic declassification after a certain number of years have elapsed. However, it is possible to circumvent the declassification schedule using security designations other than confidential, secret, and top secret. For example, the Bush administration used Sensitive but Unclassified (SBU) and the Obama administration used a category called Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI). Documents so designated are not technically classified, so they do not have to be declassified according to a schedule.

Declassification falls into three categories:

- Automatic declassification is driven by presidential Executive Order 13526 of 2009 and is triggered when documents reach an age threshold of 25 years. However, agencies can exempt or exclude documents from declassification.

- Systematic review occurs in those cases where agencies have excluded documents from automatic declassification.

- Discretionary declassification may be done in response to public interest or if an agency determines that a category of information no longer needs to be kept secret prior to becoming subject to automatic declassification.

Automatic declassification is something of a misnomer. In the automatic declassification process, material must still be reviewed to ensure that personally identifiable information (PII) is not revealed, that material that is still classified is not referred to, and that agreements with foreign governments about keeping information secret are maintained. This extensive review process results in enormous backlogs of material scheduled for declassification.

In order to speed up the declassification review process, the National Declassification Center (NDC), part of the National Archives, settled on a policy of selective declassification of the most requested records series rather than declassifying an entire group of records at once. The National Archives receives input on this from a public interest declassification board. Citizens are invited to provide input on declassification priorities.

The best evidence that automatic declassification is an ideal, not a reality, is that in 2011 the CIA released the last declassified documents from World War I (that’s over 100 years old!) related to secret writing. There are still hundreds of millions of pages of documents awaiting review from World War II and even earlier.

Once a document has been declassified, does it stay declassified? We learned after September 11, 2001 that documents can be reclassified, such as information about nuclear arsenals. In most cases, though, once a document has been released it is likely to be disseminated by an organization that specializes in replicating declassified documents. As a result, the declassified document remains publicly available in spite of efforts to reverse classification decisions. To illustrate this point, many years ago depository libraries received a document about IRS criminal investigations of cases like tax evasion. A recall was issued when it was discovered that the document was for internal use only because it revealed investigative techniques that might be of use to criminals. A librarian who filed a FOIA request for the document received a heavily redacted version. However, another individual scanned the entire unredacted document and it is now available in HathiTrust.[1]

Another complicating factor in declassification is a law known as the Kyl-Lott Amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act of 1999. It required that agencies conduct page-by-page reviews of records eligible for automatic declassification, and even previously declassified material, to check for Restricted Data and Formerly Restricted Data related to information about nuclear weapons.

Sources of Declassified Documents

Electronic Sources

- Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) is published by the Historical Office of the U.S. State Department. The volumes are currently published about 30 years following the events they cover and each volume covers a specific time period and geographic area or subject. The volumes consist of unclassified and declassified diplomatic correspondence, cables, and other documents that pertain to foreign relations. Documents come from the State Department, CIA, presidential libraries, and other government sources. FRUS is available from the State Department, HeinOnline, HathiTrust, and other online sources.

- PlusD (Public Library of US Diplomacy) is a repository of mostly restricted material obtained by public interest site WikiLeaks through various means. Researchers can search the full text of documents or browse by classification categories, date, or tags.

- Digital National Security Archive (ProQuest) The National Security Archive, based at Georgetown University, obtains documents on selected topics through FOIA requests. Most documents date from 1945 to the present. The archive holds many unpublished documents that must be viewed in its reading room. Part of its collection of declassified documents is available on its website, but libraries must subscribe to the database available through ProQuest to access its curated topical collections, searchable through added metadata.

- ProQuest’s History Vault database includes confidential files from the State Department, CIA, FBI, and military intelligence files, documents from the British Foreign Office, and other sources covering the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Declassified Documents Online (Gale) began as a microfiche set published by Carrollton Press, which collected and indexed documents that were declassified as a result of President Nixon’s Executive Order 11652 in 1972. It excluded documents that were automatically classified following the expiration of the 30-year rule, those already disseminated widely, and those appearing in FRUS.[2] It features selected declassified documents obtained from presidential libraries and federal agencies. Its editors monitor presidential libraries for the release of newly declassified documents appropriate for inclusion in the database. Most of the content is presidential documents but it also includes material from the State Department, Department of Defense, CIA, FBI, National Security Council, and other agencies.[3]

- Archives Unbound (Gale) offers access to State Department and FBI documents among many other primary sources.

- One of EBSCO’s digital archive modules is United States Bureau of Investigation Case File Archives, a collection of files from the predecessor of the FBI.

- Electronic reading rooms maintained by federal agencies and presidential libraries provide access to selected declassified documents. However, researchers must visit in person to view documents that have not been published online. Usually, there is a link for the electronic reading room on the agency’s home page. For example, the FBI’s electronic reading room is called The Vault.

The following sources may be used to view records that are not available electronically.

National Archives

The National Declassification Center at the National Archives publishes lists of recently declassified documents, and citizens are invited to provide input on which groups of records should be prioritized for declassification. Some of the declassified documents are later published in the subscription databases listed above, but for access to the bulk of declassified material, a trip to the archives is necessary.

Microform Collections

The Center for Research Libraries (CRL) holds many microfilmed sets of documents such as Documents of the National Security Council that were originally published by University Publications of America (now owned by ProQuest and available electronically through its History Vault product mentioned above). Documents can be requested from CRL through interlibrary loan. Finding aids or indexes to these collections are usually available online even though the contents of the microfilm or microfiche are not.

Gale’s Primary Source Media offers microfilm collections of John F. Kennedy’s national security files, U.S. State Department records, and other collections. A searchable finding aid is available online.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

Dating to 1966, FOIA gives citizens the right to request documents from federal executive branch agencies. It is important to remember that FOIA only applies to the executive branch, and there are nine exemptions that agencies may use to decline FOIA requests:

- Information that is classified to protect national security.

- Information related solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency.

- Information that is prohibited from disclosure by another federal law.

- Trade secrets or commercial or financial information that is confidential or privileged.

- Privileged communications within or between agencies, including those protected by the:

- Deliberative Process Privilege (provided the records were created less than 25 years before the date on which they were requested)

- Attorney-Work Product Privilege

- Attorney-Client Privilege

- Information that, if disclosed, would invade another individual’s personal privacy.

- Information compiled for law enforcement purposes that:

- Could reasonably be expected to interfere with enforcement proceedings

- Would deprive a person of a right to a fair trial or an impartial adjudication

- Could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy

- Could reasonably be expected to disclose the identity of a confidential source

- Would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions, or would disclose guidelines for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions if such disclosure could reasonably be expected to risk circumvention of the law

- Could reasonably be expected to endanger the life or physical safety of any individual.

- Information that concerns the supervision of financial institutions.

- Geological information on wells.[4]

Let’s examine some examples of information that may be withheld. The applicable exemptions are indicated in parentheses.

Intelligence Budget (National Security)

Researchers sometimes ask how much the U.S. spends on covert operations or other intelligence activities. The national intelligence budget was secret until 2012, and there is still no detail in terms of how much is spent on each function or program. It is easy to disguise intelligence expenditures. For example, during the Cold War the CIA established phony foundations to funnel money to anti-Communist propaganda programs in the U.S.[5] The CIA is an expert in hiding funds so that they cannot be traced back to the agency. To complicate matters, much of the intelligence work of the U.S. is now performed by defense contractors. Although we can learn how much goes to each contractor in total, we cannot tell how much of the funds paid to these contractors is for defense work vs. intelligence work. There is no transparency in terms of what contractors are doing and how effective it is; neither the public nor Congress can evaluate whether our tax dollars are being spent effectively on contractors who perform intelligence functions.

Geospatial Data (National Security)

An important category of information that may be subject to secrecy is geospatial data. The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, or NGA, is the official government agency that collects and controls the release of geospatial intelligence. Examples of geospatial data that may be withheld or redacted include detailed maps or imagery of military installations that might reveal functions or activities such as munitions storage, chemical weapons, or weapons testing.

You may have heard of Area 51, a large Air Force base near Groom Lake in Nevada that was an open secret for many years. Many people believe that Area 51 was where extraterrestrials were taken for study, but the consensus of military experts is that it is used for testing experimental aircraft. Satellite imagery of Area 51 was withheld or redacted for many years, fueling speculation about its purpose. Historical information about Area 51 was finally released in 2013, in response to a FOIA request. Apparently, the intelligence agencies determined that there was so much information already publicly available that they might as well release some basic information.[6]

Biosecurity and Environmental Hazards (National Security; Trade Secrets)

Biosecurity and hazardous chemicals constitute another category of information that may be withheld or restricted. Understandably, there is concern about releasing detailed information about biopreparedness, security systems, and our vulnerability to attack.

The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986 (EPCRA) requires manufacturers who use or manufacture hazardous chemicals to report the chemicals to states. Emergency responders need access to this information so that they can respond appropriately in an emergency. Large amounts of certain chemicals must also be reported to the EPA and risk management plans must be on file. However, the reports and plans are not posted online where they could be consulted by emergency planners or the general public.

Similarly, risk assessments and emergency plans for nuclear power plants could be used by terrorists to learn of vulnerabilities and help them circumvent security measures. On the other hand, area residents may not be informed about how vulnerable these plants are to meltdown or terrorist attack.

Personal Information (Privacy)

Names of confidential informants, names of people involved in human subjects research, and information like social security numbers may be redacted, or entire documents containing such information may be withheld. Agencies argue that even if names have been redacted, it may be possible for a reader to determine someone’s identity from the context, so agencies may decline to release an entire document or redact large sections, not jus the individuals’ names.

Law Enforcement

Exemptions to FOIA related to law enforcement include procedure manuals, internal rules, and interagency communications. Even an agency’s internal procedures for handling FOIA or Privacy Act (PA) requests can be secret, so that the public has no way of understanding the thought process or policy that goes into the handling of these requests. In fact, some FOIA experts believe that agencies are deliberately secretive about their internal handling of FOIA or PA requests so that they don’t give any clues to potential requestors about how to construct their requests more effectively.

Political Secrecy

Many people believe that a lot of government information is withheld not because of the legitimate reasons that fall under the exceptions to FOIA, but because of political secrecy. For example, General Taguba’s 2004 report on an investigation of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in Iraq, which revealed that Army personnel tortured and humiliated Iraqi prisoners, was withheld, but it was later leaked to the news media. In spite of the leak, the Army still wouldn’t declassify it. In fact, members of the armed services are prohibited from referring to classified information, even if it is publicly available, resulting in the odd situation of students at military academies being unable to consult or discuss classified documents that were published by WikiLeaks.

An example of political secrecy involving a civilian agency is a book written by a former FBI agent claiming that if the FBI had done its job correctly, the attacks on U.S. targets on September 11, 2001 could have been avoided. He was required to withdraw the book, but it’s hard to say whether the FBI’s objections were politically motivated or based on national security concerns.[7] Government employees who work with classified information are typically subject to non-disclosure agreements and are governed by laws limiting what they can disclose. Therefore, if a former CIA agent were to write a memoir, it would be subject to review by the agency, and if it objected to certain sections, the author would have to omit them.

FOIA Improvement Act of 2015

The most recent update to FOIA occurred with the FOIA Improvement Act of 2015 (Public Law 114-185). It mandated a “presumption of openness,” required agencies to publish released documents, and limited the applicability of Exemption 5 to documents produced less than 25 years earlier, among other modifications that were designed to streamline the FOIA process and reduce backlogs. Prior to the 2015 law, the Open Government Act of 2007 established the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), designed to serve as the FOIA ombudsman and mediate disputes between agencies and requesters.

Using FOIA to Request Documents

Both FOIA.gov and the National Security Archive offer guidance and tips for FOIA requesters. Before submitting a FOIA request, it’s important to verify that the desired documents are not already publicly available by reviewing the documents available through each agency’s FOIA reading room and checking the other sources listed above. Sometimes, agencies can be of help by informing researchers directly that a FOIA request is necessary. Note that fees charged for research and copies may vary depending on the affiliation of the requester.

Even with the legislative improvements to FOIA, there is no centralized administration of FOIA requests, so there is no consistent approach between agencies. Therefore, it’s important for researchers to correctly identify the agencies that are most likely to hold the desired records. These inconsistencies in releasing documents have sometimes resulted in the very same document being released by a presidential library but withheld by the CIA. Redactions of the same document released by two different agencies may be wildly different due to differences in declassification policies or simply the personal characteristics of the declassifier. One strategy employed by successful FOIA requesters has been to request the same documents from multiple agencies, then use the releases of one agency to argue for the release of additional information from other agencies.

FOIA.gov allows you to generate a basic report telling how many FOIA requests each agency received and how many were processed, but it doesn’t reveal how many were denied. We don’t know whether backlogs have decreased because agencies are getting through more requests, or because they are simply saying “no” and not spending time looking for the information requested in the first place.

Case Study: Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

By Christopher Moratin

Learning Objectives:

- Learn how to write a FOIA request

- Learn how to file a FOIA request to Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

Question: How do you write a FOIA request and submit it to the CIA?

Search strategies:

CIA website: https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/node/256459

Example:

A patron is interested in obtaining information about the new ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi. Specifically, the patron is interested in obtaining old and current photographs of the new ISIS leader including any information about Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi that confirms his identity.

The Freedom of Information Act is a tool that citizens of a democratic government can use to ensure transparency and accountability within their government. Anyone, U.S. citizen or not, is allowed to make a request for any currently existing record.[8] Learning how to write a FOIA request is simple. Most federal agencies accept FOIA requests electronically. The U.S. Department of Justice maintains a directory of FOIA contacts for all federal agencies.

Agencies also post information that has been requested and approved for release in digital reading rooms. Therefore, it is advisable to see if the documents you are seeking are already available. Given that we are using CIA as an example, it would behoove us to first check the agency’s web page for guidance. There, we find a sample FOIA request letter and helpful hints about submitting a records request. Notably, the CIA does not accept FOIA requests by email, only by postal mail or fax. You can also submit a request electronically using the online request form. Note that attachments are not permitted.

Requests directed to CIA should include the following:

- Your personal contact information: your first and last name, address, city, and country.

- Identify the requestor category: Educational/scientific, commercial, news media, or other.

- A detailed, specific description of the records you are requesting. In this case, you could state that you are seeking photographs of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi and any information about him that confirms his identity.

- Finally, you should indicate the maximum dollar amount that you will pay in fees. You can request a fee waiver if you can demonstrate that your request is in the public interest. More information about fees and waivers for the CIA can be found on the Fees and Waivers page.

Tools for Filing FOIA Requests

- MuckRock, a non-profit collaborative news site, offers the FOIA Machine, which allows researchers to submit and track FOIA requests at both the federal and state/local levels. It can be viewed as a sort of social media site for FOIA requests, where researchers can share their inquiries and results with other researchers.

- FOIA.gov provides an interface to submit FOIA requests to participating agencies. However, some agencies do not currently allow requesting through FOIA.gov. In those cases, FOIA.gov provides instructions for submitting requests directly to the agency.

Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR)

MDR is another method to request access to documents, specifically those that are classified. Under the provisions of Executive Order 12958, researchers can request that agencies declassify specified documents before they are subject to automatic declassification. The process can take longer than a FOIA request because an agency has up to one year to respond to an MDR request. In addition, MDR requests must be very narrowly constructed, whereas FOIA requests can be much broader. Furthermore, when an MDR request is denied, the requester cannot sue, but the decision can be appealed to a review board.

Leaks

In addition to documents being released through MDR or FOIA requests, a third avenue for the release of documents is leaks. The Pentagon Papers, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg, is one of the most famous examples of classified documents that were leaked to the news media. WikiLeaks has obtained and published over 10 million pages of restricted and unrestricted documents by obtaining them from individuals who had access to them. News organizations occasionally obtain and republish leaked documents or compile summaries of them.

Privacy Act

The Privacy Act (PA) is related to FOIA because it gives individuals the right to request government records about themselves and allows individuals to request amendment or correction of records about them. If you were to request information about the IRS’s files on you, that would be a PA request, not a FOIA request. FOIA would cover requests for other types of information like systems, procedures, or statistics compiled or maintained by the IRS. The PA, passed in 1974, is an attempt to document and make known the records systems under agencies’ control that collect personally identifiable information. It also establishes a process through which agencies must publish information about their systems of records in the Federal Register, and they must maintain lists of systems and notices of changes to these systems. PA issuances are also compiled every two years and are a collection in govinfo.gov.

FOIA Case Studies

Athan Theoharis is a researcher who’s written several books about the FBI. This section draws on his book A Culture of Secrecy: The Government Versus the People’s Right to Know, which is a discussion of several researchers’ experiences using FOIA, mostly with the FBI.[9] Theoharis interviewed several authors who’d done research using FBI files. In addition to fighting crime, the FBI has investigation files on subjects like Prohibition, organized crime, investigations of people suspected of being disloyal (e.g., Germans, Italians, Japanese, Communists), campaigns to discredit people like Martin Luther King, Jr., and files on many celebrities. Theoharis enumerated reasons why FOIA requests to the FBI were unsuccessful:

- The volume of information was too great.

- It was too difficult to write a request that only resulted in files the requesters wanted.

- Requesters sometimes couldn’t afford fees charged by the FBI.

- Finding aids were not very helpful or were unavailable because they were classified or secret (for example, they contained names of informants).

- The FBI sometimes claimed not to have files that later turned up.

- In some cases, the FBI refused to release documents that had already been released by presidential libraries, even when this was pointed out to them.

One researcher covered in Theoharis’s book wrote about trying to find the arguments the government devised to prevent John Lennon, a former member of the Beatles, from immigrating to the U.S. After Lennon’s death in 1981, the FBI took ten years to release his file, claiming the national security exemption. It’s hard to imagine national security considerations in Lennon’s case, so the researcher concluded that the real motivation was probably political.

The CIA is especially notorious for not being forthcoming. Authors reported that they got the One example of the frustrations of seeking CIA documents relates to MK-ULTRA, which was a 1950s-1960s program of experiments related to mind control, including dosing unsuspecting people with LSD. The CIA destroyed files related to MK-ULTRA, so it wasn’t possible to find out who in the CIA was involved or the identities of the unwitting subjects. Later, however, the CIA found 8,000 pages of documents related to the experiments, leading to questions about the agency’s credibility when they claimed not to have the documents. Like the FBI, the CIA has refused to release documents that were previously released by presidential libraries. Judges have tended to side with CIA when their disclosure practices have been challenged in court.

The FRUS series, mentioned above, is the diplomatic history of the U.S. Volumes are supposed to be published within 30 years of events they describe, but the time gap has increased in recent years, mainly because of the declassification process done by military intelligence agencies and especially the CIA. Subsequent releases of declassified documents have prompted revisions of certain volumes. A volume covering relations with Iran during 1951-1954 presents a case study. Initially published in 1989, the volume lacked key information about U.S. covert operations in Iran. The State Department subsequently produced a revised volume in 2016, but the Secretary of State at the time, John Kerry, did not permit its publication due to concern about negotiations with Iran related to its nuclear programs. Finally, the volume was released in 2017.[10] Previously, volumes concerning Indonesia and relations between Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey had been withheld by the State Department due to political sensitivity surrounding U.S. covert operations. [11]

One need look no further than the National Security Agency (NSA) for examples of between-agency inconsistency in releasing documents. Most of the NSA’s documents are exempt from disclosure. The agency has withdrawn documents from presidential libraries, but later copies of some of them were found at the National Archives. Its fees can be prohibitive, and it can take up to five years to get any sort of response from the NSA. The NSA refused to release documents related to the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1968, in which a CIA spy ship claimed it was fired upon by a North Vietnamese vessel. The incident was used as an excuse to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Even though some of the documents were released in the Pentagon Papers, the NSA refused to release related documents.

In the early days of email, the Reagan administration was the first to have records in the form of electronic mail. When Reagan left office in late 1980s, the National Archives intended to delete the electronic email and preserve paper copies. Eventually, they were persuaded to keep the electronic records. Following Reagan, the outgoing George H. W. Bush administration did not want the Clinton administration to have access to its email records. They made a secret deal with the Archivist of the U.S. and removed tapes and hard disks that contained Bush’s email. Even the Clinton administration claimed that emails were not presidential documents but rather federal records and therefore not subject to the Presidential Records Act (PRA). Clinton also claimed that the National Security Council was not an agency and therefore not subject to the PRA. As you can see, presidents and agencies have developed creative legal arguments to avoid releasing information.

Open Government

Peter Shane made the following distinction between open government and freedom of information: “The ‘open data’ movement is, at its core, really about taking data in the hands of government and making it more adaptable. The freedom of information movement is really about securing access to data, adaptable or not, that increases accountability.”[12] The Sunlight Foundation, an organization that promotes transparency and open government, identified the characteristics of open government as completeness, primacy, timeliness, ease of physical and electronic access, machine readability, non-discrimination, use of commonly owned standards, licensing, permanence and usage costs.[13] President Obama promised to have the most transparent administration ever, and early in his presidency he issued a memorandum on transparency and open government that reversed some of the policies established by president George W. Bush. In 2013, this policy was further refined with an executive order, Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government Information, designed to make government data more accessible. The goals of Obama’s policy were to:

- Publish government information online

- Improve the quality of government information

- Create and institutionalize a culture of open government

- Create an enabling policy framework for open government[14]

Agencies were also required to create open government plans that detailed how they would open their records and data. In spite of his directives, President Obama was not successful in changing the institutional culture of the executive branch. In fact, experts agree that government secrecy is entrenched, and no president has managed to effect sweeping changes that would result in a truly open government. Scholars and journalists generally agree that the administration of President Donald J. Trump has tended not to emphasize transparency. At the same time, the Trump administration has not made any significant policy decisions affecting transparency.[15]

Open Data

An important component of open government is open data. In addition to Data.gov, various agencies have open data portals to provide access to their data products. In 2013, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) directed agencies with at least $100 million in annual research and development to create plans for providing public access to peer-reviewed scientific publications and data resulting from federally funded research. In response, agencies created public access plans detailing the means by which they would comply with the directive. For instance, the Department of Energy (DOE) unveiled DOE Pages, a database of journal articles and accepted papers funded by DOE.

Congress and Open Government

As we have seen, FOIA does not apply to Congress, but there are other laws that require the disclosure of certain information by members of Congress. The federal Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (LDA) requires lobbyists to register and report contributions. Furthermore, former member of Congress who work as lobbyists must report their contacts with sitting members.

The House and Senate have rules on gift disclosures, financial disclosures, legal expenditures reporting, and reporting on foreign travel expenditures. Note that privately funded foreign travel is not reported on the travel expenditures report; the member would have to list the trip on a gift disclosure. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate provide access to recent disclosure reports on their websites. Historical financial disclosure reports are available in the U.S. Congressional Serial Set. Government-funded travel expenditures are reported in the Congressional Record and are also available as stand-alone reports. It is striking that members of Congress must report their own and their spouse’s income, banking and investment accounts, real property, debts, and assets, while the president is not required to do so.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, even though there is a tremendous amount of information available online, it’s only the tip of the iceberg. Our duty as librarians is to help patrons understand which types of information are readily available, what must be requested, and what is not likely to be released. Most patrons will be constrained by time or money, in which case our task becomes helping them find relevant information that has already been published.

Librarian’s Library

Ginsberg, W., Carey, M. P., Halchin, L. E., & Keegan, N. (2012). Government transparency and secrecy: An examination of meaning and its use in the executive branch. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/secrecy/R42817.pdf

This report provides a synopsis of federal laws related to transparency in the executive branch.

National Security Archive. (2008). Effective FOIA requesting for everyone. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//nsa/foia/foia_guide/foia_guide_full.pdf

The staff at National Security Archive has abundant experience in requesting information through FOIA. This publication is considered the most comprehensive guide to submitting FOIA requests, with tips for using the most effective techniques to produce the desired documents.

- U.S. Internal Revenue Service. (1996). 75 years of IRS criminal investigation history, 1919-1994. Washington, D.C.: Internal Revenue Service. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015043243156 ↵

- Morehead, J. (1999). Introduction to United States Government Information Sources (6th ed.). Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited. ↵

- Golderman, G. & Connolly, B. (2018). Government surveillance and declassified documents. Library Journal 143(1), 124-124. ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Information Policy. What are FOIA exemptions? https://www.foia.gov/faq.html ↵

- Saunders, F. S. (2000). The cultural cold war: The CIA and the world of arts and letters. New York: New Press. ↵

- Tozer, J. L. (2013). Area 51 declassified. Armed with Science Blog, September 2, 2013. http://science.dodlive.mil/2013/09/02/area-51-declassified/ ↵

- Miller, J. (2002, May 11). F.B.I. agent suing bureau for barring book on terror. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/05/11/us/fbi-agent-suing-bureau-for-barring-book-on-terror.html ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice. FOIA FAQ. https://www.foia.gov/faq.html; Caro, S. (2019). Fun with FOIA and the Zen of waiting. https://www.fdlp.gov/fall-2019-federal-depository-library-conference ↵

- Theoharis, A. G. (1998). A culture of secrecy: the government versus the people’s right to know. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ↵

- Aftergood, S. (2017). Iran 1953 covert history quietly released. Secrecy News, 16 June 2017. https://fas.org/blogs/secrecy/2017/06/iran-frus-release/ ↵

- Aftergood, S. (2001). “Suppressed” FRUS volume published. Secrecy News, 10 August 2001. https://fas.org/sgp/news/secrecy/2001/08/081001.html ↵

- Shane, P. (2012). What do we want from open government and what the heck is open government? Jotwell: The Journal of Things We Like (Lots). https://adlaw.jotwell.com/what-do-we-want-from-open-government-and-what-the-heck-is-open-governmen/ ↵

- The Sunlight Foundation. Ten principles for opening up government information. http://sunlightfoundation.com/policy/documents/ten-open-data-principles/. ↵

- Ginsberg, W., Carey, M. P., Halchin, L. E., & Keegan, N. (2012). Government transparency and secrecy: An examination of meaning and its use in the executive branch. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/secrecy/R42817.pdf ↵

- Ellington, T. C. (2018). Transparency under Trump: Policy and prospects. Public Integrity (2018): 1-14. ↵

Refers to the CIA ship Glomar Explorer, which was sent on an expedition to recover a Soviet nuclear submarine in 1974. When journalists asked about the expedition, they received response that the CIA could “neither confirm nor deny” its existence. This phrase is now known as the “Glomar response.”