2 Statutory Law and Congressional Materials

Gwen Sinclair

Learning Objectives

- Understand the variety of publications that are issued in the process of lawmaking

- Develop an understanding of the categories of legislative publications and learn how to locate them

- Become familiar with indexes for congressional publications

- Understand the different forms in which laws are published and how to locate them

- Become familiar with the content and management of congressional papers

- Learn about legislative agencies and their publications

- Understand the legislative process at the national level

- Learn how to locate or compile a legislative history

This chapter covers the federal legislative process, statutes, and congressional publications produced in the process of lawmaking. It also examines the content and availability of congressional papers collections. In chapters 10–11, we will examine legislative material at the state and local level.

U.S. Constitution

The Constitution forms the basis for U.S. constitutional law. The National Archives hosts a facsimile edition of the Constitution accompanied by a text version and background information. Constitution of the United States: Analysis and Interpretation (CONAN) presents the legislative history of the Constitution along with analysis and court interpretations. GPO also publishes a pocket-sized version of the Constitution that is freely available to federal depository libraries and is also available for purchase.

Locating the Text of Federal Laws

Public Laws

Public laws, which form the basis of statutory law, have general applicability to the public. To find the text of a law as it was originally passed by Congress, consult U.S. Statutes at Large. Statutes are arranged in public law number order, by session of Congress. The citation format is [volume no.] Stat. [page no.]. You can locate a law using the Statutes at Large citation, the public law number, the index to the volume, or do a keyword search. Free access to Statutes at Large from the 1st through 81st Congress is available from the Law Library of Congress. Volumes from the 82nd Congress (1951) to the present are available in govinfo.gov.

Because many laws amend existing laws, reading a session law is sometimes not very useful, so one must consult the law as it reads after being incorporated into the existing law (see United States Code below). Researching laws can be very complex, especially in the case of omnibus legislation, which amends numerous laws that don’t necessarily have anything to do with each other. If you only have the common name of a law instead of the public law number or Statutes at Large citation, you can consult the Legal Information Institute’s Table of Popular Names to find the citation. For example, if we are searching for the Huna Tlingit Traditional Gull Egg Use Act, we find the Statutes at Large citation, 128 Stat. 1749, (volume 128, page 1749), and the public law number, 113-142.

Examples

- An Act to Allow for the Harvest of Gull Eggs by the Huna Tlingit People within Glacier Bay National Park in the State of Alaska (Huna Tlingit Traditional Gull Egg Use Act)

- An Act to Prevent Pernicious Political Activities (Hatch Act)

Private Laws

In contrast to public laws, private laws apply only to one person or entity. Many cover claims against the government or immigration matters. Because they do not have general applicability, they are not incorporated into the United States Code. An example of a private law is 56 Stat. 1226, passed in 1942 to enable the author Leslie Charteris, known for writing spy novels featuring Simon Templar (the Saint), to be admitted to the U.S. for permanent residence. Charteris, being half Chinese, was prohibited from immigrating to the U.S., but his status as an author enabled him to persuade Congress to make an exception to immigration laws that barred Chinese from becoming permanent residents.

Compilations of Federal Laws

The primary codification of federal laws is the United States Code (U.S.C.). The citation format is [title no.] U.S.C. [section no.] It is compiled by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel (OLRC) of the U.S. House of Representatives and arranges laws by subject in 51 titles or broad subject areas. The U.S.C. cites the various public laws that have been compiled into each section. It is issued every six years and is updated by supplements. Be aware that there is a time lag between the passage of a law and its inclusion in U.S.C. Therefore, researchers who need the most recent version of U.S.C. are directed to use the one on the OLRC website.

Compilations of federal laws are also issued by the congressional committees that have jurisdiction over that area of law. The Law Library of Congress maintains links to the current editions of these compilations and other law-related committee prints.

Annotated versions of the U.S.C. used by attorneys include citations to court cases, law review articles, and other material that expand understanding of a particular area of law. The two main commercially published annotated versions are United States Code Annotated (U.S.C.A.), published by West, and United States Code Service, published by LexisNexis.

Legislative History

Legislative histories consist of the bills, documents, reports, committee prints, committee hearings, floor debate in Congress, voting records, and presidential statements associated with the passage of a law. Researchers often use them to gain insight into the passage of a piece of legislation, to determine legislative intent, or to learn how a particular provision was inserted into a law.

Components

Legislation is listed in the Congressional Record and House or Senate Journal upon its introduction. The sponsor may make a statement, which is also published in the Congressional Record. Sometimes, identical legislation is introduced in both chambers simultaneously, or multiple competing versions of a bill may be introduced in each chamber. The bill may be referred to one or more committees. Some legislation is never referred to a committee by the House or Senate leadership or, once referred, does not advance out of a committee. Frequently, no explicit statement is published explaining the failure of the bill, so it may be difficult to determine why it didn’t advance. News reports sometimes reveal the reasons behind a bill’s failure.

Congressional committees may conduct hearings on a bill, either by itself or together with several other related bills. Of course, hearings on national security matters are secret and are not available. Committees may amend or “mark up” a bill and issue a revised version. The committee may “report out” the bill to the entire chamber, in which case a House or Senate report is published. However, there have been instances where no committee report was issued.

Once a bill has made it out of committee, a floor vote may be taken. The bill may be amended on the floor, and the amendments and votes on the bill and on the amendments are recorded in the Congressional Record. If the House and Senate pass different versions of a bill, members of a conference committee are appointed to resolve differences. The conference committee may issue a report. This is another point at which legislation may fail if the two sides are not able to reach an agreement. Once passed, the bill goes to the president, who may either sign or veto the bill. If he signs it, he may issue a presidential signing statement. Presidential signing statements can be found in the Compilation of Presidential Documents or the Public Papers of the President. If he vetoes a bill, a veto message is transmitted to Congress.

Published Legislative Histories

Legislative histories have been published for many major pieces of legislation. Usually, these published histories reproduce or list all of the documents related to the legislation, such as bills, hearings, House and Senate reports, Congressional Record pages, and presidential signing statements. Legislative histories may be compiled by the pertinent agency or by the Congressional Research Service.

Examples

- A Legislative History of the Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972

- A Legislative History of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and Its Amendments

The ProQuest Congressional database includes legislative histories for legislation passed from 1970 to the present. They may or may not include the full text of all of the component documents. Subscribers to ProQuest Congressional Digital Edition have access to the full texts of all of the component documents of each legislative history. The HeinOnline Legislative History Library is another source for the full text of all component documents. Legislative histories of landmark legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 may be covered in academic or popular literature, e.g., The Longest Debate: A Legislative History of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[1]

If no published legislative history exists, one must identify all pertinent documents piece by piece. A brief legislative history appears at the end of each law in the Statutes at Large, which can be the jumping-off point. Consult the Congressional Record and House or Senate journal for documents created at each step of the legislative process. For a detailed description of doing legislative history from scratch, consult Georgetown Law Library Legislative History Tutorial or Law Librarians’ Society of Washington, DC Federal Legislative History Research.

Case Study: Puʻukoholā Heiau National Historic Site

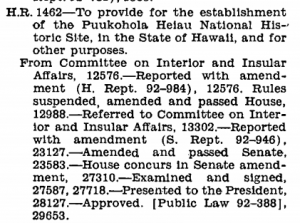

Senators Hiram Fong and Daniel Inouye of Hawai‘i submitted S. 3627, and Representative Patsy Mink of Hawai‘i introduced H.R. 15721 in 1970 to establish Puʻukoholā Heiau National Historic Site. Although both bills were referred to the respective Senate and House committees on Interior and Insular Affairs, neither made it out of committee in that session of Congress. In the following session, Rep. Mink introduced H.R. 1462 on January 22, 1971, and the senators introduced the corresponding Senate bill, S. 459 on January 29, 1971. Again, the bills were assigned to the House and Senate committees on Interior and Insular Affairs, which in turn assigned them to the pertinent subcommittees.

Both committees reported out the bills favorably with amendments after the respective subcommittees conducting hearings. The House subcommittee held hearings not only in Washington, D.C. but also in Kailua-Kona in Hawaiʻi, “to hear the views of local people in regard to the establishment of the Puukohola Heiau National Historic Site.”[2] The hearing text reproduced the text of the bill drafted by Rep. Mink; a budget estimate for development of the site; testimony of Rep. Mink, local individuals, and representatives of interested organizations; and a map of the site.

The bill as originally submitted would have authorized the Department of the Interior to acquire 75 acres of land for the site. The Senate hearing on S. 459 included written testimony from Senators Inouye and Fong. Both stated that they did not object to a House amendment to increase the limit on the acreage to 100. However, the Senate subcommittee did not agree with the House amendment, and it increased the acreage only to 77 acres in accordance with the Department of the Interior’s request as stated in its letter, which was reproduced in both the hearing and the committee reports.

On April 17, 1972, the House passed H.R. 1462. However, S. 459 was not taken up by the full Senate until June 30. It accepted the subcommittee’s amendment and sent its version of the bill to the House. On August 8, the House concurred with the Senate amendment and approved the bill in its final form. President Nixon signed the bill into law on August 17, 1972.

Figure 1 shows the Congressional Record entry for the history of H.R. 1462, which provides a brief legislative history. The numbers following each action refer to the page number in the Congressional Record where the action was recorded.

Congressional Publications—Bills

Thousands of bills are introduced in each legislative session, but only a few even make it to the first step, which is being assigned to one or more committees for consideration. Frequently, companion bills are introduced into both houses of a legislature. These bills may be identical, but sometimes, as with tax cut measures, there are significant differences. Researchers often want to review different versions of bills to determine how the legislation changed as it made its way through the legislative process.

Most bills never become law. It often happens that a committee chairperson declines to move a bill forward and is said to have “killed” it. Another common reason for lack of success is that a bill is introduced at the behest of a constituent or to make a political point, even though the sponsor knows that it has no chance of getting a hearing. For instance, Senator Rand Paul introduced the One Subject at a Time Act (S. 3359) in 2012 to force drafters of legislation to limit each bill or resolution to one subject. There were no cosponsors, and the bill died in the Senate Rules and Administration Committee.

If a bill is unsuccessful, it can be reintroduced into the next legislative session. Some bills are introduced year after year. For example, bills to add a constitutional amendment to ban the burning of the U.S. flag are introduced perennially.

Table 1. Sources for Full Text of Congressional Bills

|

Dates |

Source |

|

1993–present |

|

|

1973–present |

|

|

1789–present |

|

|

1789–present |

ProQuest Digital U.S. Bills and Resolutions |

Although bills introduced in recent decades are readily available online, older bills can be difficult to obtain except through interlibrary loan. Only a few large research libraries have comprehensive collections of bills on microfiche or through digital subscription. Sources of the full text of congressional bills are listed in Table 1. Several sources that one can consult to find either the full text or summaries of bills are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Sources for Historical Congressional Bill Text or Summaries

| Dates | Source |

| 1873–present | Congressional Record |

| 1936–1990 | Digest of Public General Bills and Resolutions |

| varies | Legislative histories |

| 1789–present | U.S. Congressional Serial Set |

| 1921–1995 | Westlaw U.S. Government Accountability Office’s legislative histories |

Congressional Publications—Resolutions

Resolutions are a type of legislation used for actions such as acknowledging an organization or individual, but they may also be used to make a political statement. Resolutions can be simple, joint, or concurrent. Simple resolutions express the opinions of the House or Senate. House resolutions are abbreviated H. Res. and those of the Senate, S. Res. They are often used to commemorate individuals, groups, or events, such as H. Res. 1044 (IH)—Congratulating the Honolulu Little League Baseball team of Hawaii on winning the 2018 Little League Baseball World Series Championship. They do not go to the president for approval.

Joint resolutions are similar to bills in that they must be passed by both chambers. One important difference between bills and joint resolutions is that joint resolutions to amend the Constitution are not forwarded to the president for his signature, but are sent to the states for ratification. Joint resolutions are abbreviated as H.J. Res. or S.J. Res. depending upon which chamber originated the measure.

A concurrent resolution is used to express a fact, principle, or opinion of Congress. Measures are abbreviated as H. Con. Res. or S. Con. Res. Like simple resolutions, concurrent resolutions do not go to the president for a signature. Resolutions are published in Statutes at Large.[3]

Examples

- House Joint Resolution: H.J. Res. 45 (104th Congress),Proposing a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution of the United States

- House Concurrent Resolution: H. Con. Res. 189 (104th Congress), Expressing the sense of the Congress regarding the importance of United States membership and participation in regional South Pacific organizations.

Bill Tracking

Following the progress of a current bill is relatively easy. The Library of Congress’ site Congress.gov allows researchers to view all of the legislation sponsored or cosponsored by a member of Congress and follow each bill’s progress through the legislative process.

For a broad brushstrokes view of the legislative process, let’s examine a recent bill, the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, introduced on January 8, 2019 by Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. Using Congress.gov, it is easy to read the text of the bill and follow its progress through both houses of Congress and to the president.

The Congressional Research Service composes a bill summary for each bill, which provides a brief overview of its provisions. Like many bills, S. 47 covered a wide variety of actions, including land transfers, wildlife conservation, wilderness designations, the National Volcano Early Warning and Monitoring System, and the renaming of the Pearl Harbor National Memorial and the Honouliuli National Historic Site. Looking under Related Bills, one can see that 124 individual bills were merged into this omnibus act. Broad bipartisan support allowed S. 47 to bypass the the hearing and amendment process in Senate committees.

During the debate in the Senate, a few floor amendments were passed. The Senate passed the bill and the roll call vote of 92 yeas and 8 nays was recorded. The bill was then referred to the House of Representatives, which also conducted a floor debate and passed the bill 363–62. Finally, the bill was sent to the president, who signed it into law on March 12, 2019, when it became Public Law 116–9, the 9th law passed in the 116th Congress.

For a different experience in bill tracking, try the free GovTrack.us site. GovTrack is an independent research company that uses public data to track legislation and present analysis and statistics about legislation. Users can sign up for alerts in order to follow specific pieces of legislation, members of Congress, or congressional committees.

Resources for Congressional Voting Records

Often, researchers want to know who voted for or against a bill or wish to compare votes by party affiliation. The following resources can be helpful:

- Congress.gov provides access to roll call votes beginning with the 101st Congress (1989–1990).

- The Congressional Record contains recorded votes going back to 1873. Use govinfo.gov to get the full text.

- The Congressional Record’s predecessor titles, Annals of Congress, Register of Debates, and Congressional Globe, cover the period 1789–1873. Use the Library of Congress’ A Century of Lawmaking site to search these publications.

- The House journal and Senate journal record individual votes on bills.

- Project VoteSmart allows you to find voting records on key legislation for individual members of Congress going back to the 1990s.

- CQ Federal is a subscription database published by CQ Roll Call, a longtime publisher of legislative bill tracking and analysis tools.

Legislative Committees

As you might imagine, the volume of bills introduced into Congress is far too great for all of the members to consider. That’s where specialized committees come in. Legislators are appointed to serve on one or more committees, which are typically constituted by subject areas. Committees serve several important roles in a legislative body. First and foremost, they consider legislation referred to them for vetting. Committee chairs are very powerful in most legislative bodies, and they can hold a bill and decline to schedule it for a hearing, in which case the bill is said to have “died in committee.” Another event that can signal the death of a bill is when the committee members vote against the measure. Committees can also make amendments to bills.

Legislative committees do more than consider bills, though. An important function of committees is to conduct investigations of executive branch agencies, current events, or even industries. Investigations may be handled by regular standing committees, or the legislature may appoint members to a special or select committee to investigate a particular event or issue.

Examples

- Select Committee on the Events Surrounding the 2012 Terrorist Attack in Benghazi

- Special Committee on Investigations of the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs

The U.S. Senate, like many state senates, is also responsible for approving nominees for executive branch appointments. A nominee will be vetted by the relevant committee before the nomination is considered by the full Senate. For instance, nominations for attorney general or federal judge would be heard by the Committee on the Judiciary. Committee members question the nominees and hear testimony from others about them. Senators sometimes use hearings as an opportunity to air grievances against the nominee or the office to which the person has been nominated. The recent hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee regarding the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court are an excellent example of how senators use hearings as a soapbox.

Another function of legislative committees is to investigate the need for legislation covering a particular issue or to evaluate the effectiveness of existing legislation. Committees sometimes conduct oversight hearings about government programs or the execution of specific laws.

Examples

- Administration of Native Hawaiian Home Lands: Joint Hearings before the Select Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, and the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, First Session.

- Hearings on the Nomination of Ruth Bader Ginsburg to be Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, July 20, 21, 22, and 23, 1993.

- Hurricane Katrina: Waste, Fraud, and Abuse Worsen the Disaster.

Legislative bodies generally have two types of committees: standing committees and select or special committees. Standing committees may change from one legislative session to the next, or committees may be combined or reorganized. For example, the House Committee on Military Affairs was combined with the House Committee on Naval Affairs to form the House Committee on Armed Services. Committees may have subcommittees like the House Committee on Armed Services, Subcommittee on Readiness. Select and special committees may have popular names, such as the Dies Committee (official name: House Un-American Activities Committee), which investigated communism in the federal government. To find the official names of committees, consult Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: a Checklist.[4] The Congressional Directory lists the membership of committees in each session of Congress.

Joint committees consist of members of both houses. They can be temporary or permanent, like the Joint Economic Committee or the Joint Committee on Printing, which oversees the Government Publishing Office. Typically, the leadership of permanent joint committees passes back and forth from the House to the Senate.

When the House and Senate need to reconcile different versions of a bill that each has passed, each chamber appoints members to an ad hoc conference committee. Members of conference committees are listed in the Daily Digest section of the Congressional Record.

While most hearings are conducted in Washington, D.C., committees sometimes conduct field hearings, in which some or all of the committee members travel to one or more cities to hear testimony from local residents and politicians. Field hearings are of interest because they include the testimony of ordinary citizens.

Examples

- Field Hearing on the State of VA Care in Hawaii: Hearing before the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, United States Senate, One Hundred Ninth Congress, Second Session

- Field Hearing in New York: The Empire (State) Strikes Back: Creating 21st Century Manufacturing Opportunities in New York City: Hearing before the Committee on Small Business, United States House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourteenth Congress, Second Session

Congressional Publications—Hearings

Published congressional hearings include transcripts of the statements of committee members, questioning of witnesses, and written statements of witnesses. They may also include letters from organizations or individuals and reproductions of news articles or other reports. Sometimes, they contain the full text of the bill under consideration. More commonly, they list the amendments made by the committee. Markup hearings contain the amended text of bills as revised, or “marked up,” by the committee members.

Not all congressional hearings are published, though. Committees sometimes conduct their business in executive session. In addition, hearings are published at the discretion of the committee chair, and some are published years after the date of the hearing. Some hearings are not published, in which case a copy may be obtained from the National Archives’ Center for Legislative Archives for a fee. Of course, committee hearings that concern national security matters, such as weapons system authorizations or intelligence appropriations, may not be publicly available. It’s also important to note that published hearings may not include all of the appendices or exhibits referred to during the hearing. Often, to save money on printing costs, hearings were published without these ancillary documents.

The full text of hearings is available in govinfo.gov starting in 1995, and a few hearings from 1985 to 1995 are also available. Many libraries have digitized the hearings of selected committees, and these can usually be found in HathiTrust or Internet Archive. Most pre-1975 hearings are not freely available online, though, and the only electronic access is through the subscription database ProQuest Congressional Digital Edition. HeinOnline also includes the full text of many hearings in its Legislative History Library. The advantages of full-text searching of congressional hearings cannot be understated, because many hearings run into hundreds or thousands of pages and often have no index. In a few cases, a commercial publisher has published an index to a series of congressional hearings. For example, Greenwood Press compiled an index to hearings about the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.[5]

C-SPAN, a service provided by the U.S. cable industry, broadcasts House proceedings. Its video archive goes back to 1979 when it began broadcasting from the House. C-SPAN2 provides live television coverage of floor proceedings in the Senate. Its video archive goes back to 1986, when it started broadcasting from the Senate. Note that not all hearings are broadcast. Videos of some hearings may be available on committee websites.

While Congress has periodically issued indexes to committee hearings, the ProQuest Congressional database and its print counterpart, CIS Index, are the only comprehensive indexes to congressional publications. Beyond listing the title, corporate author, date, session of Congress, and subject keywords, the database also includes names and affiliations of witnesses, an important feature when a researcher seeks a particular individual’s testimony. As good as it is, even CIS Index is missing a few publications, however.

Congressional Publications—Committee Prints

Committee prints are publications prepared for the use of committee members and their staffs. They often provide in-depth research or background information about a topic for the committee’s consideration. Committee prints are a sort of catch-all category that encompasses a variety of different types of publications, including reports of study missions to foreign countries, committee rules, investigative reports, serial publications such as legislative calendars, compilations of laws, and legislative histories. Because they are considered internal documents, many committee prints are not distributed to federal depository libraries, so some libraries subscribe to ProQuest Congressional Digital Edition to gain access. In the past, several services provided microfiche copies of prints to subscribers. In addition, many libraries were members of the Documents Expediting Project of the Library of Congress, through which they received committee prints. Consequently, large research libraries may have extensive collections of prints. Currently, most committee prints are not freely available online.

Examples

- Study Mission to Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, Laos, and Hawaii (January 3-14, 1990): Report of the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control, One Hundred First Congress, Second Session

- Compilation of Federal Laws Authorizing Education Assistance Explicitly for American Indians and Other Native Americans (Legislation as Amended through December 31, 1975)

Congressional Research Service Reports

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is the research arm of the Library of Congress and it conducts research at the request of members of Congress. Committee prints sometimes reproduce CRS reports, which may give an overview of an issue, provide historical background for legislation, or cover issues for the consideration of Congress. In 2018, Congress passed a law that requires the Library of Congress to publish most CRS reports online. This development will dramatically affect the availability of CRS reports. However, the law’s provisions are not retroactive, so librarians will still have to rely on several other sources for older CRS reports, as described in this LibGuide.

Examples

- S. 147/H.R. 309: Process for Federal Recognition of a Native Hawaiian Governmental Entity

- The U.N. Convention Against Torture: Overview of U.S. Implementation Policy Concerning the Removal of Aliens

- State and Local “Sanctuary” Policies Limiting Participation in Immigration Enforcement

Congressional Publications—Committee Reports

Reports describe actions taken by a committee, such as amendments, and they include statements from executive branch agencies giving the administration’s views, pro or con, on proposed legislation. They may provide insight into the rationale for passage of a bill and the amendment process, but this is not always the case. Reports also examine the regulatory and budget impacts of legislation. If a committee votes against a bill, no report is issued, so it can be difficult to learn why a bill died in committee. Congressional reports are abbreviated H.rp. or S.rp. followed by a number. In order to locate a report, one must know the date or session of Congress, since the numbering restarts with each legislative session.

Congressional Publications—Documents

Even though they’re called documents, House or Senate documents include reports from executive branch agencies. In the 19th century and early 20th century, most executive branch publications were issued as congressional documents. In addition, many organizations and bodies, such as the Boy Scouts of America, have been required to submit annual reports to Congress which were published as House or Senate documents.

Documents are usually abbreviated H.doc, S.doc, etc., followed by a number, and, like reports, one must know the date or session of Congress in order to retrieve them. Important Congressional documents include:

Examples

- Economic Report of the President

- Memorial tributes to members of Congress, presidents, etc.

- Senate and House manuals

- Our Flag

- How Our Laws Are Made

Congressional reports and documents are collectively bound into volumes known as the U.S. Congressional Serial Set. While reports and documents are available online from 1975 to the present in govinfo, older reports may only be available through expensive subscription databases published by HeinOnline, ProQuest, and Readex. Some Serial Set volumes are now freely available in HathiTrust. You may be surprised to learn that not all congressional reports have been cataloged, so some are still not searchable in WorldCat and one must use other databases or indexes such as CIS US Serial Set Index[6] to locate them.

Congressional Publications—Congressional Record

The Congressional Record (CR) is usually described as the verbatim record of the proceedings on the floor of Congress: speeches, amendments, procedural maneuvering, votes, and so forth. Its predecessor titles are Annals of Congress, Register of Debates, and Congressional Globe. What is less well-known is that members can submit “extension of remarks,” material that was not part of the floor proceedings. Remarks may include a statement of the member’s opinion about a piece of legislation or other matter brought before the House or Senate. Extensions may also include news articles or ephemera like pamphlets.

The CR records each bill introduced in each chamber and the action taken, such as referrals to committees, floor amendments, and votes. There are two editions of the CR: the daily CR, published each day that Congress is in session, and the bound CR, a compilation of the daily issues. Caution: when presented with a citation to the CR, it is necessary to know whether the citation is for the daily or bound edition, because the pagination doesn’t match! The citation format for the CR is [volume] Cong. Rec. [page no.]. The daily CR includes a section called Daily Digest that summarizes the actions taken that day. The index to the CR include the section History of Bills and Resolutions, which allows a researcher to locate a particular bill and to see all of the actions taken on the bill along with references to the page numbers where each action appears in the CR.

Fortunately for librarians, all volumes of the CR are available in govinfo. Libraries may also have the CR in print or microform, or through subscription access to ProQuest Congressional Digital Edition, LLMC Digital, or HeinOnline. Beware, though: these databases only provide the uncorrected Optical Character Recognition (OCR) processed text for older volumes, so keyword searches may fail, especially for personal or place names.

Congressional Publications—Journals

House and Senate journals, published at the end of each session, document the daily actions that occurred in each chamber. They can answer questions like “Which bills were considered on a given date?” or “Was this bill voted on, and what was the vote?” Journals also list each bill and its sponsors, who voted for and against each bill, and procedural matters.

Congressional Publications—Rules and Manuals

Each chamber has its own rules, precedents, and customs that govern its organization and procedures. Rules determine, for example, whether a simple majority or a two-thirds majority is required to pass a measure. The Senate Manual, prepared by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, is the compilation of the rules, laws, and resolutions that govern Senate procedures. The House of Representatives has its own rules, published in the House Manual at the beginning of each session after the rules have been adopted. In contrast, the Senate does not adopt new rules at the beginning of each session, since its members have overlapping terms.

In addition to stating the rules of each chamber, the manuals also contain statistics, lists of the leadership, lists of standing committees, laws that affect congressional procedures, regulations related to members’ travel, financial disclosures, and use of by members. Congressional committees may also publish rules that govern the operations of the committee.

Congressional Publications—Official Congressional Directory

The Official Congressional Directory is issued each session and lists each member of Congress. It gives brief biographical information about each member, along with a portrait. It is more than a list of the members of Congress, though. You can also find:

- Lists of standing committees and subcommittees and their members

- Cabinet members and leadership of executive branch agencies, boards, and commissions

- Leadership of legislative branch agencies

- Judges in the federal judiciary

- International organizations and their leadership

- Foreign diplomatic offices in the U.S.

- Maps of congressional districts

Legislative Agencies

Congress oversees several legislative branch agencies:

- The Congressional Budget Office produces reports about the budgetary effects of legislation and analyses of budget issues. For example, CBO responded to a request from Senator Susan Collins for an analysis of the budgetary effects of S. 534, the Immigration Rule of Law Act of 2015, a law that would have prevented the administration from expanding Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

- The Government Accountability Office (GAO), formerly known as the General Accounting Office, is a nonpartisan agency within Congress that oversees how government funds are expended. It issues reports about the effectiveness and administration of federal laws and programs and issues opinions and decisions about government contracting.

- The Government Publishing Office (formerly Government Printing Office) is overseen by the Joint Committee on Printing, although GPO’s director is appointed by the president. It is responsible for official U.S. government publishing. It also publishes the U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual.

- The Library of Congress and its Congressional Research Service perform research for members of the House and Senate. The Law Library of Congress maintains legal reference materials and researches matters of law.

- The House and Senate each have their own libraries that maintain copies of all of the congressional publications relevant to that chamber.

Online Availability of Legislative Materials

Increasingly, congressional material is available online for free. However, some publications, especially congressional hearings and bills, vary in their online availability. Other sources for legislative material include:

- Law libraries

- Regional or large federal depository libraries

- Center for Legislative Archives of the National Archives

- Library of Congress or Law Library of Congress

- Your own representatives and senators may obtain copies of documents on your behalf

Congressional Papers

The papers of members of Congress contain everything from draft legislation to gifts given to the member. In contrast to presidential papers, no law requires members of Congress to deposit their papers or even to retain them. Nonetheless, many members have chosen to deposit their papers with libraries or archives in their home states or at an alma mater. Papers may be divided between more than one institution. The Center for Legislative Archives of the National Archives maintains an index of archival repositories and congressional collections to direct researchers to libraries holding papers of U.S. senators and representatives.

In addition to providing information about a member of Congress, congressional papers are very important for research in legislative history, historical events, and specific issues considered by Congress. For example, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) (also known as the Dies Committee after its chair, Martin Dies) conducted investigative hearings to uncover the extent of communist and fascist penetration in the U.S., especially in government. A researcher interested in HUAC would probably want to consult the Martin Dies Papers at the Texas State Archives.

Congressional papers may be closed for varying periods of time at the discretion of the member or his or her family, up to 30 years in some cases. More often than not, papers are deposited without processing funds. Therefore, some papers such as those of Senators Fong and Akaka of Hawaiʻi are partially or completely unprocessed, so finding aids may not be available. In some cases, a foundation has raised funds to make papers available and even put on events or exhibits to commemorate the member’s service. For example, the UHM Library exhibited “A Time of Great Testing: Senator Daniel K. Inouye and the Democratic National Convention of 1968” with help from the Daniel K. Inouye Institute.

Even when a member’s papers have been completely processed and are not closed, not all of the papers may be publicly available. For example, case files and correspondence with constituents may not be available due to privacy concerns. Congressional papers may also contain classified material, which requires special handling by the National Archives.

Librarian’s Library

Boyd, A. M. & Rips, R. E. (1949). United States government publications. (3rd ed. rev.). New York: The H.W. Wilson Company.

Chapters IV and V, which cover Congressional material from Colonial times to the 1940s, are particularly useful for researching legislative history of older bills. The authors present very thorough discussions of Congressional publications, their content, and how they are indexed.

Canon, D. T., Nelson, G., & Stewart, C. H. (2002). Committees in the U.S. Congress, 1789-1946. Washington, D.C: CQ Press.

Nelson, G. & Bensen, C. H. (1993). Committees in the U.S. Congress, 1947-1992. Washington, D.C: Congressional Quarterly.

These two guides make it easy to see the composition of Congressional committees or to learn on which committees a specific member of Congress served.

CQ Press. (2012). Guide to Congress (7th ed.). Washington, D.C.: SAGE.

A very comprehensive overview of Congress, its history, customs and traditions; powers, rules and procedures; ethics and lobbying; and many other topics.

Sevetson, A. (Ed.). (2013). The Serial Set: its make-up and content. Bethesda, MD: ProQuest.

Andrea Sevetson, an expert on the U.S. Congressional Serial Set, and co-authors explain what the Serial Set is and what it contains, with many beautiful color illustrations.

Sullivan, J. V. (2007). How our laws are made. H. Doc. 110-49, 110th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CDOC-110hdoc49/pdf/CDOC-110hdoc49.pdf

Detailed explanation of types of legislation, how legislation moves through Congress, various rules that impact the progress of legislation, and congressional publications.

United States. Congress. Joint Committee on Printing. Biographical directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present http://bioguide.congress.gov/

This guide gives brief biographical information about members of Congress and explains where to find their papers if they were deposited at a research institution.

- Whalen, C. W. & Whalen, B. (1985). The longest debate: A legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Cabin John, MD; Washington, D.C.: Seven Locks Press. ↵

- United States House of Representatives, Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation. (1972). Puukohola Heiau National Historic Site: Hearings before the Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives, ninety-second Congress, first session, on H.R. 1462, a bill to provide for the establishment of Puukohola Heiau National Historic Site in the state of Hawaii, and for other purposes. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ↵

- Sullivan, J.V. (2007). How our laws are made. H. Doc. 110-49, 110th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C. : Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CDOC-110hdoc49/pdf/CDOC-110hdoc49.pdf ↵

- Stubbs, W. (1985). Congressional Committees, 1789-1982: A checklist. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ↵

- Smith, Stanley H. (1990). Investigations of the attack on Pearl Harbor: Index to government hearings. New York: Greenwood. ↵

- Congressional Information Service. (1975). US serial set index. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Information Service. ↵

The franking privilege allows members of Congress to send mail under their signatures without postage.