2.1 Demand

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain demand, quantity demanded, and the law of demand

- Identify a demand curve and a demand schedule

- Identify factors that affect demand

- Graph demand curves and demand shifts

First, let’s focus on what economists mean by demand, what they mean by supply, and then how demand and supply interact in a market.

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists use the term demand to refer to the amount of particular good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is fundamentally based on needs and wants—if you have no need or want for something, you won’t buy it. While a consumer may be able to differentiate between a need and a want, from an economist’s perspective they are the same thing. Demand is also based on the ability to pay. If you cannot pay for it, you have no effective demand. By this definition, a minimum wage worker would not have effective demand for a brand new Tesla.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service is called price. The total number of units that consumers would purchase at that price is called the quantity demanded. A rise in price of a good or service almost always decreases the quantity demanded of that good or service. Conversely, a fall in price will increase the quantity demanded. For example, when the price of a gallon of gasoline increases, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to home. Economists call this inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded the law of demand. The law of demand assumes that all other variables that affect demand (which we explain in the next module) are held constant.

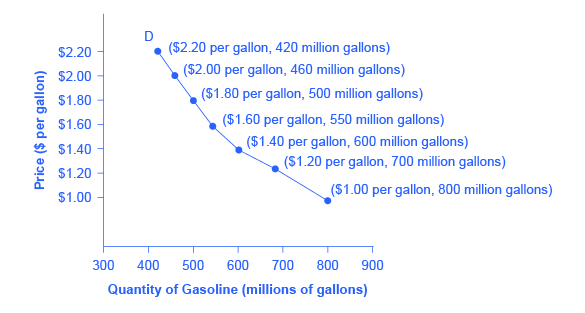

We can show an example from the market for gasoline in a table or a graph. Economists call a table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table 2.1, a demand schedule. In this case we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline. We measure the quantity demanded in millions of gallons over a specific time period (for example, per day or per year) and over some geographic area (like a state or a country). A demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 2.2, with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. (Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable [x] goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable [y] goes on the vertical. Economics is not math).

Table 2.1 shows the demand schedule and the graph in Figure 2.2 shows the demand curve. These are two ways to describe the same relationship between price and quantity demanded.

|

Price (per gallon) |

Quantity Demanded (millions of gallons) |

|

$1.00 |

800 |

|

$1.20 |

700 |

|

$1.40 |

600 |

|

$1.60 |

550 |

|

$1.80 |

500 |

|

$2.00 |

460 |

|

$2.20 |

420 |

Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. Demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Confused about these different types of demand? Read the next CLEAR IT UP feature.

CLEAR IT UP

Is demand the same as quantity demanded?

In economic terminology, demand is not the same as quantity demanded. When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices. This is illustrated by a demand curve or a demand schedule. When economists talk about quantity demanded, they mean only a certain point on the demand curve, or one quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the curve and quantity demanded refers to the (specific) point on the curve.

What Factors Affect Demand?

We defined demand as the amount of a particular product a consumer is willing and able to purchase at each price. That suggests at least two factors in addition to price that affect demand. Willingness to purchase suggests a desire, based on what economists call tastes and preferences. If you neither need nor want something, you will not buy it. Ability to purchase suggests that income is important. Professors are usually able to afford better housing and transportation than students, because they have more income. Prices of related goods can also affect demand. If you need a new car, the price of a Honda may affect your demand for a Ford. Finally, the size or composition of the population can affect demand. The more children a family has, the greater their demand for clothing. The more driving-age children a family has, the greater their demand for car insurance, and the less for diapers and baby formula.

These factors matter for both individual and market demand as a whole. Exactly how do these various factors affect demand, and how do we show the effects graphically? To answer those questions, we need the ceteris paribus assumption.

The Ceteris Paribus Assumption

A demand or supply curve is a relationship between two, and only two, variables: quantity on the horizontal axis and price on the vertical axis. The assumption behind a demand curve or a supply curve is that no relevant economic factors other than the product’s price are changing. Economists call this assumption ceteris paribus, a Latin phrase meaning “all other things being equal.” Any given demand or supply curve is based on the ceteris paribus assumption that all else is held equal. A demand curve or a supply curve is a relationship between two, and only two, variables when all other variables are kept constant. If all else is not held equal, then the laws of supply and demand will not necessarily hold, as the following Clear It Up feature shows.

CLEAR IT UP

When does ceteris paribus apply?

We typically apply ceteris paribus when we observe how changes in price affect demand or supply, but we can apply ceteris paribus more generally. In the real world, demand and supply depend on more factors than just price. For example, a consumer’s demand depends on income and a producer’s supply depends on the cost of producing the product. How can we analyze the effect on demand or supply if multiple factors are changing at the same time—say price rises and income falls? The answer is that we examine the changes one at a time, assuming the other factors are held constant.

For example, we can say that an increase in the price reduces the amount consumers will buy (assuming income, and anything else that affects demand, is unchanged). Additionally, a decrease in income reduces the amount consumers can afford to buy (assuming price, and anything else that affects demand, is unchanged). This is what the ceteris paribus assumption really means. In this particular case, after we analyze each factor separately, we can combine the results. The amount consumers buy decreases for two reasons: first because of the higher price and second because of the lower income.

How Does Income Affect Demand?

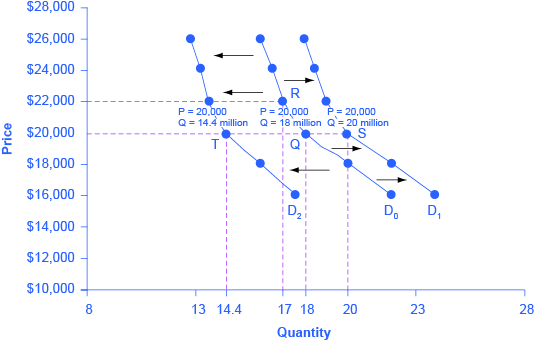

Let’s use income as an example of how factors other than price affect demand. Figure 2.3 shows the initial demand for automobiles as D0. At point (Q), for example, if the price is $20,000 per car, the quantity of cars demanded is 18 million. D0 also shows how the quantity of cars demanded would change as a result of a higher or lower price. For example, if the price of a car rose to $22,000, the quantity demanded would decrease to 17 million, at point (R). The original demand curve (D0), like every demand curve, is based on the ceteris paribus assumption that no other economically relevant factors change. Now imagine that the economy expands in a way that raises the incomes of many people, making cars more affordable. How will this affect demand? How can we show this graphically?

Return to Figure 2.5. The price of cars is still $20,000, but with higher incomes, the quantity demanded has now increased to 20 million cars, shown at point (S). As a result of the higher income levels, the demand curve shifts to the right to the new demand curve (D1), indicating an increase in demand. Table 2.2 shows clearly that this increased demand would occur at every price, not just the original one.

|

Price |

Decrease to D2 |

Original Quantity Demanded D0 |

Increase to D1 |

|

$16,000 |

17.6 million |

22.0 million |

24.0 million |

|

$18,000 |

16.0 million |

20.0 million |

22.0 million |

|

$20,000 |

14.4 million |

18.0 million |

20.0 million |

|

$22,000 |

13.6 million |

17.0 million |

19.0 million |

|

$24,000 |

13.2 million |

16.5 million |

18.5 million |

|

$26,000 |

12.8 million |

16.0 million |

18.0 million |

Now, imagine that the economy slows down so that many people lose their jobs or work fewer hours, reducing their incomes. In this case, the decrease in income would lead to a lower quantity of cars demanded at every given price, and the original demand curve (D0) would shift left to D2. The shift from D0 to D2 represents a decrease in demand: at any given price level, the quantity demanded is now lower. In this example, a price of $20,000 means 18 million cars sold along the original demand curve, but only 14.4 million sold after demand fell. When a demand curve shifts, it does not mean that the quantity demanded by every individual buyer changes by the same amount. In this example, not everyone would have higher or lower income and not everyone would buy or not buy an additional car. Instead, a shift in a demand curve captures a pattern for the market as a whole.

In the previous section, we argued that higher income causes greater demand at every price. This is true for most goods and services. For some—luxury cars, vacations in Europe, and fine jewelry—the effect of a rise in income can be especially pronounced. A product which sees a demand rise when income rises, and vice versa, is called a normal good. A few exceptions to this pattern do exist. As incomes rise, many people will buy fewer generic-brand groceries and more name-brand groceries. They are less likely to buy used cars and more likely to buy new cars. They will be less likely to rent an apartment and more likely to own a home. A product that sees demand fall when income rises, and vice versa, is called an inferior good. In other words, when income increases, the demand curve shifts to the left.

Other Factors That Shift Demand Curves

Income is not the only factor that causes a shift in demand. Other factors that change demand include tastes and preferences, the composition or size of the population, the prices of related goods, and even expectations. A change in any one of the underlying factors that determine what quantity people are willing to buy at a given price will cause a shift in demand. Graphically, the new demand curve lies either to the right (an increase) or to the left (a decrease) of the original demand curve. Let’s look at these factors.

Changing Tastes or Preferences

From 1980 to 2014, the per-person consumption of chicken by Americans rose from 48 pounds per year to 85 pounds per year, and consumption of beef fell from 77 pounds per year to 54 pounds per year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Changes like these are largely due to movements in taste, which change the quantity of a good demanded at every price; that is, they shift the demand curve for that good—rightward for chicken and leftward for beef.

Changes in the Composition of the Population

The proportion of elderly citizens in the United States population is rising. It rose from 9.8% in 1970 to 12.6% in 2000, and will be a projected (by the U.S. Census Bureau) 20% of the population by 2030. A society with relatively more children, like the United States in the 1960s, will have a greater demand for goods and services like tricycles and day care facilities. A society with relatively more elderly persons, as the United States is projected to have by 2030, will have a higher demand for nursing homes and hearing aids. Similarly, changes in the size of the population can affect the demand for housing and many other goods. Each of these changes in demand will be shown as a shift in the demand curve.

Changes in the prices of related goods such as substitutes or complements can also affect the demand for a product. A substitute is a good or service that we can used in place of another good or service. As electronic books become more widely available you would expect to see a decrease in demand for traditional printed books. A lower price for a substitute decreases demand for the other product. For example, in recent years as the price of tablet computers has fallen, the quantity demanded has increased (because of the law of demand). Since people are purchasing tablets, there has been a decrease in demand for laptops, which we can show graphically as a leftward shift in the demand curve for laptops. A higher price for a substitute good has the reverse effect.

Other goods are complements for each other, meaning we often use the goods together, because consumption of one good tends to enhance consumption of the other. Examples include breakfast cereal and milk; notebooks and pens or pencils; golf balls and golf clubs; gasoline and sport utility vehicles; and the five-way combination of bacon, lettuce, tomato, mayonnaise, and bread. If the price of golf clubs rises, since the quantity demand for golf clubs falls (because of the law of demand), demand for a complementary good like golf balls decreases, too. Similarly, a higher price for skis would shift the demand curve for a complement good like ski resort trips to the left, while a lower price for a complement has the reverse effect.

Changes in Expectations about Future Prices or Other Factors That Affect Demand

While it is clear that the price of a good affects the quantity demanded, it is also true that expectations about the future price (or expectations about tastes and preferences, income, and so on) can affect demand. For example, if people hear that a hurricane is coming, they may rush to the store to buy flashlight batteries and bottled water. If people learn that the price of a good like coffee is likely to rise in the future, they may head to the store to stock up on coffee now. We show these changes in demand as shifts in the curve. Therefore, a shift in demand happens when a change in some economic factor (other than price) causes a different quantity to be demanded at every price. The following Work It Out feature shows how this happens.

WORK IT OUT

Shift in Demand

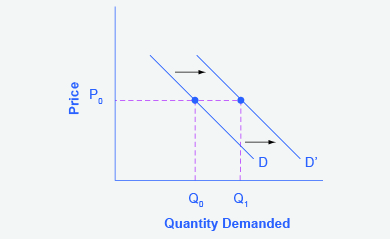

A shift in demand means that at any price (and at every price), the quantity demanded will be different than it was before. The following is an example of a shift in demand due to an income increase.

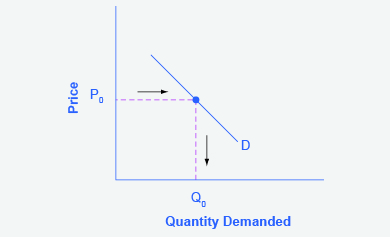

Step 1. Draw the graph of a demand curve for a normal good, like pizza. Pick a price (like P0). Identify the corresponding Q0. See an example in Figure 2.4.

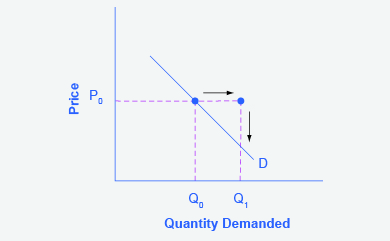

Step 2. Suppose income increases. As a result of the change, are consumers going to buy more or less pizza? The answer is more. Draw a dotted horizontal line from the chosen price, through the original quantity demanded, to the new point with the new Q1. Draw a dotted vertical line down to the horizontal axis and label the new Q1. Figure 2.5 provides an example.

Step 3. Now, shift the curve through the new point. You will see that an increase in income causes an upward (or rightward) shift in the demand curve, so that at any price the quantities demanded will be higher, as Figure 2.6 illustrates.

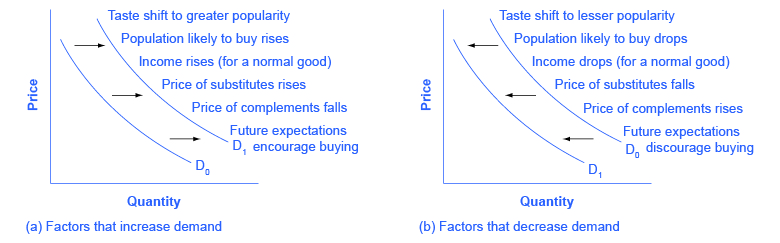

Summing Up Factors That Change Demand

Figure 2.7 summarizes six factors that can shift demand curves. The direction of the arrows indicates whether the demand curve shifts represent an increase in demand or a decrease in demand. Notice that a change in the price of the good or service itself is not listed among the factors that can shift a demand curve. A change in the price of a good or service causes movement along a specific demand curve, and it typically leads to some change in the quantity demanded, but it does not shift the demand curve.

When a demand curve shifts, it will then intersect with a given supply curve at a different equilibrium price and quantity. We are, however, getting ahead of our story. Before discussing how changes in demand can affect equilibrium price and quantity, we first need to discuss shifts in supply curves.

SELF-CHECK QUESTIONS

- What does a downward-sloping demand curve mean about how buyers in a market will react to a higher price?

- Will demand curves have the same exact shape in all markets? If not, how will they differ?